Note: My translation of the first book appears at the bottom of this post.

Last week, I began with book III in my translation of Tzara’s long poem, Approximate Man, but now I’m stepping back to begin going through it in order. There are nineteen books in all, running around 150 pages total, and with this one complete I’m just a bit over 10% done. I expect to slow down a bit with my translations after this post, but—rather than shifting gears yet again—I want to stick with Tzara to end this opening month of Out of Its Wooden Brain on a more consistent note.

Also, while translating, I’ve been reading in Marius Hentea’s TaTa Dada: The Real Life and Celestial Adventures of Tristan Tzara (MIT, 2014), and I’ve begun to understand some of the reasons for Approximate Man’s relative obscurity. As Hentea writes, the poem was printed in 1931 in a very small edition of only 510 copies. From what I can tell, it was not reprinted until the 1968 Gallimard edition, five years after Tzara’s death. Presently, Tzara’s complete work appears to be out of print even in French (last edition I have found was printed in multiple volumes in 1991), and I’m assuming his estate just hasn’t been managed very well. But I’m still investigating all this.

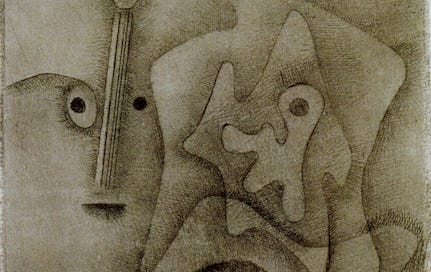

I also found that the original tiny edition of the poem came with illustrations by Paul Klee. Here is the main image of Klee’s that is available online:

According to Hentea, it also appears that the mode of this poem was short-lived. Tzara published it during a brief reconciliation with the Surrealists, but by 1935 he had broken with them again and devoted himself increasingly to the Communist party (who were in conflict with major Surrealists). The in-fighting among these French intellectuals was imply insane, and it seems that denunciation, public attacks, declared war, and betrayal were simply how one moved in these circles. In particular, Tzara had major disagreements with André Breton—a king-pin figure—regarding the role of poetry in a revolutionary context. Hentea explains that, contrary to those who argued for the revolutionary power of art itself, Tzara believed that one had to decisively choose committed political action and not lie to oneself about what poetry and art can achieve.

However, this hard-line stance was not intended as a rejection of art. As Tzara writes in Grains et issues (“Seeds and Harvests”) in 1935, “It is not necessary to renounce poetry to conduct revolutionary social actions, but being revolutionary is an inherent necessity to being a poet” (qtd. in Hentea 237). Further, he continued to maintain that poetry should preserve its autonomy and should not be tainted by writing overtly didactic, political work (i.e. Tzara never wrote agitprop, and he absolutely did not write in a mode of Socialist Realism). As Hentea notes, critics of the time were baffled by his stance, and it brought about his decisive break with Breton. And it is easy to conclude Tzara was simply trying to have it both ways — to be both “the better communist” and “the better poet,” and playing each against the other — but I’m not sure that assessment is fair.

Ultimately, Tzara seems to have believed that poetry’s relationship to communism was such that only a future state of full communism could realize poetry’s total power. But of course, insofar as Tzara was writing under capitalism—in fact, under encroaching fascism—he seems to have believed that all poetry, even his own, was destined to be partial, fragmented, and a mere approximation of what this liberated imagination under communism would look like. And yet, rather than abandon poetry, it was necessary to continue practicing poetry now, as a way of exercising imagination and preventing its dying out. Where he parted with the Surrealists was precisely on the issue of whether or not such continued artistic practice was enough. Against them, or his apprehension of them, he believed that an artist must do more than make art: they must be materially committed to revolution; further, they must continually acknowledge and grapple with art’s corrupted and partial nature. For Tzara, art must continue to exist, but it should never become an escape or surrogate, and it should never be mistaken for the front lines. He felt that the Surrealists, by falling into these intellectual traps, had betrayed what they professed to stand for.

Now, I should note that I do not necessarily agree with Tzara on any of this. I’m simply trying to provide context for the poem here and illuminate where he was coming from, and I’ll be digging into all of this stuff further in the future. As I do so, my conclusions about him will surely be updated. But already it’s clear that, despite the ecstatic results of much of his work, Tzara held a position of profound ambivalence and inner conflict, and that this illuminates the poem’s pervasive air of lamentation and dissatisfaction.

*