Approximate Tzara

On translating Tristan Tzara’s epic surrealist poem, "L’Homme approximatif" (Approximate Man)

Note: A translation of Book Three of Tzara’s epic poem appears at the end of this post. The rest of the poem will appear in installments.

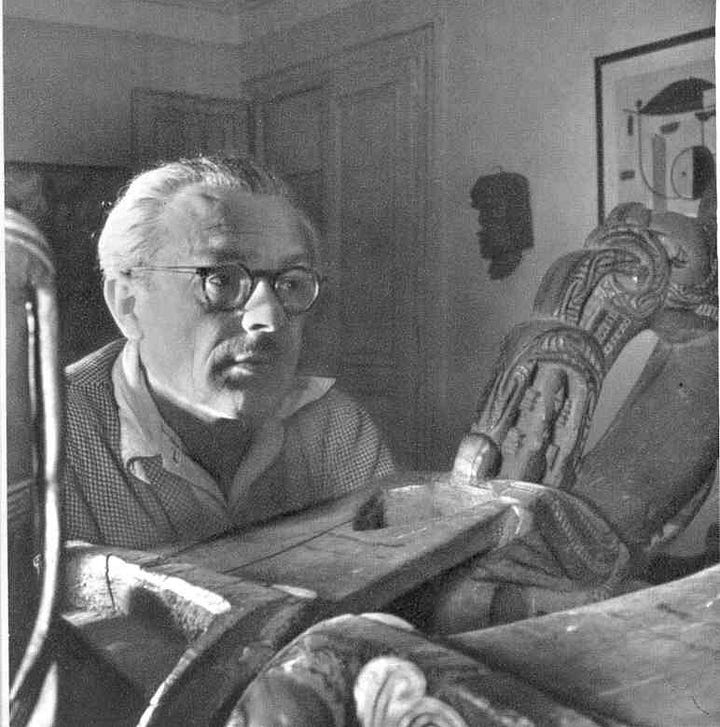

Romanian-born poet Tristan Tzara (1896-1963) is best known for helping found Dadaism, writing many of its manifestoes and poems, and being one of the foremost avant-garde artists of Europe. Plenty more could be said about his significance here, but I don’t want to write an encyclopedia entry, and you can read about him on Wikipedia. The reason for this post is to explain how and why I came to begin translating his epic poem published in 1931, L’Homme approximatif (“Approximate Man”), a neglected work of extraordinary imaginative power.

Sadly, I’d never paid Tzara any mind until the last three years. I had of course heard his name – it’s not easily forgotten — and I was aware that William Burroughs vaguely credited the cut-up technique to Tzara. And as a student, both undergrad and grad, I always found his name invoked in various historical glosses of the avant-garde. But in all these cases, the name always seemed to be mentioned in passing, as though he were an unpromising footnote. And I never once heard someone — teacher, friend, or peer — say that they read him. Perhaps this says more about me and my environment than it does about Tzara’s legacy, but I would wager that my experience is not that unusual in the US.

It was not until around 2019, when I became intrigued by the convergence between early Surrealism and communism, that I began to look into his work. While André Breton is a primary figure in this politicized context, I found that Tzara also later moved among the Surrealists and — evolving from his more nihilistic early period in Dada — began to formulate his poetics in Marxist terms. In fact, in the 1930s, he was blending Jungian theories of the unconscious with Marxist materialist theory (something I myself had been dabbling with in my essay on psycho-materialism). Also, as stated above, he also wrote an entire epic, L’Homme approximatif, (“Approximate Man,” published in 1931, but dated to 1925-30 by Tzara himself) in a fluent Surrealist style quite different from his more disjunctive Dada works (although these, too, are worth reading). Although 20th century poetic epics are usually well-known sources of critical debate, I had never heard anyone mention this text before. I was intrigued. When I finally took a look at the poem, I was overwhelmed by its beauty and strangeness. It is clearly a virtuosic work of surrealist imagination, and it is sustained at a high level of intensity across 150 pages.

A Fifty Year Old Version

To my knowledge, the only full translation of the work in English was done by Mary Ann Caws in 1973—fifty years ago. Caws has completed a lifetime of invaluable translation and scholarly work on Surrealism, and the edition of her translation reprinted by Black Widow Press in 2005 contains some of her documentary and critical work on the poem as well. She also provides this decent summary of what one can expect from the poem:

The spontaneous astonishment of Dada is replaced by a more carefully structured epic which has as a basis . . . [the] dramatic plight of man told in an accumulation of images, refrains, fugal rhythms, narrative, litany of plaints, and majestic descant. . . . Tzara works and reworks his poetry into an odd combination of the sentimental and the bizarre . . . . [We find frequent] images associated with the sky or the seasons, with death and dream, and with water. As in other surrealist writings, they create an atmosphere of the fluid state, the liberated consciousness called poetry. . . [And yet one also finds] Tzara's doubts concerning the role of poetry. (Caws 11-12)

On this last point, it is worth quoting Tzara biographer Marius Hentea: “The duality of language, radiant vision yet also empty vessel, creates a constant opposition that makes it impossible to collapse the poem into a single meaning” (229). In short, the poem is a phantasmagoria, and yet Tzara continually interrogates his own powers of imagination even as he indulges them in exhilarating fashion.

Anyone setting out to translate Tzara in English owes Caws an enormous debt of gratitude, and I’m no exception. Without her work, I’d never have read Approximate Man. However, because I read as a poet and not a scholar, I have to admit to finding multiple passages of her translation which—to my mind—lacked energy and style. Eventually, I grew frustrated enough to purchase a cheap Gallimard paperback edition to compare the French original. After a bit of puzzling through—a mixture of Google translate, my own limited grasp of French, comparison with Caws, and my own instincts as a poet—it became clear to me that I could create a new version that was 1) useful and accurate, 2) distinct from Caws, and 3) more suitable to my taste. And so…

Methods, Disclaimers, etc.

…in undertaking this, my ultimate goal is to make an exciting poem in English out of Tzara’s language. Granted, I am always mindful of the literal meaning, and I do all I can to preserve grammatical structures and to replicate his rhythm, pacing, sounds, and sense; I spend a lot of time puzzling over single word choices and appropriate syntax, pairing original sounds with mine, and considering other possibilities. However, when faced with a choice between an awkward but faithful rendering and an excitingly torqued one, I’ll almost always take the latter (as long as it doesn’t stray too far from Tzara’s larger tone, style, and purpose). A purely literal rendering is a scholarly aid, but it often destroys a poem, and I’m trying to create a poem in English out of this—something alive on the page, not something that seems to keep pointing away to a source text you don’t have.

Also, let me note that all of this is in process. I am not presenting this as the result of my long study into Tzara; rather, this is how I’m studying him. The poem still contains many mysteries to me, and translating it is how I’m exploring them. Similarly, I’m still learning about the exact political situation between Surrealism and the French Communist Party in the 1930’s, and I hope to share what I learn about all of this here. But one thing is clear: Tzara is a highly enigmatic figure, and it is not easy to pin him down as representative of any one cultural or political current.

A few final notes for now:

I am starting with book three because, for some reason I can’t remember, that is where I began with my translation. Later, I read in Caws that section three was likely written first and “is nearest in conception to the starting point for the entire poem” (253). Also, I find it more exciting than book one, so for the uninitiated this seems like a good way to begin.

I was surprised to find asterisks separating the sections of verse in the Gallimard edition, something Caws omits. I keep these asterisks as I feel they make a significant change to the poem’s pacing and the way smaller sections are framed.

Re: the poem’s style, Tzara uses no punctuation. Sometimes he writes beyond syntactical control, but other times he is using sentences that have clear beginnings and endings. So if you find the syntax becoming blurred, this is not a fault of my translation abilities, but an intentional feature of Tzara’s delirious style. He also uses repetition and refrain to create motifs across whole sections/chapters of the book, building musical echoes and re-establishing points of departure for his linguistic explorations.