Going Into the Collage

Some thoughts on poetry, collage, and visual art (w/a gallery of images)

Before I get started here, just a brief update. At the peak of busy-ness in mid-November—with dozens of poetry books being made and shipped, a poetry reading being arranged, and multiple classes online going on—I got sick with a nasty sinus infection that cost me a few days. That knocked out my plan to record a podcast episode this month, as my voice sounded like garbage right around the time I’d hoped to record. (You can almost hear the sad trombone...) But I do have at least 3 solid episodes ready to go, and several more sketched out for the coming months, I just need time to sit down and record them. So be on the look out.

So where does that leave us, here and now, in the middle of this post? Well, I’ve been wanting to share some of the collages I worked on last spring, and this seems like as good a time as any. In a way, I’ve always known that collage was how my mind naturally worked, and although I’ve dabbled in it over the years, I’d never really studied techniques and worked at it until this spring. Sometime in May, I got seized by a need to make collages that was unlike anything I’ve known in a long time, and it was all I did and thought about for a few weeks. My apartment was a disaster zone, as I was also moving at the time: not only were all my belongings in boxes piled in my living room, but the remaining surfaces were littered with scraps of paper, images, books, X-acto blades, pastels, paints, etc. I would start messing with a collage and get lost for hours—and the result was often chaotic and repulsive mess. In fact, inhabiting a state of quasi-insane messiness and becoming was a major lesson from this experience. And I want to discuss that a bit here.

As I said, I feel like my mind has always naturally worked via collage. Maybe I’m ret-conning here, but at the very least, there has always been a strongly visual aspect to how my mind operates, and it’s one I’ve suppressed—sometimes for good reason. In fact, when I first tried writing in a literary way, I was guided by a weird synaesthesia: the words that felt right to me were distinctly blue, and I felt a powerful need to avoid words that felt red or yellow. I eventually had to get over this, and this added layer of extreme subjectivity in my relationship to language has caused many difficulties, but it also is the source of much of my love of language. I’ve spent many years trying to sort out how to control my language use while still finding inspiration in it, and feeling that that inspiration was distinctly related to something more visual and play-oriented.

Much of this goes back to a childhood habit of image collecting. In my elementary and junior high years, when I was still consumed with my love of basketball and baseball, not only did I fill album after album with trading cards, but I began cutting out pictures of sports heroes and tacking them up on a bulletin board. The use of bulletin boards continued for years, well after leaving sports behind, and I covered them with thumbtacked images of everything from insects to nuclear reactors to writers and poets. I loved the visual texture of several images thrown together, and I liked watching the way that some arrangements changed over time, mutating through familiarity. And while it involved an aesthetic sensitivity, it simply felt like play—it something I just liked to do.

This appreciation for chance, surprise, and visual play is something I struggled to express through writing. I simply couldn’t make the connection between this random play with pictures and the more self-conscious handling of language. Partly this has to do with my own temperament, but it has also to do with the nature of language itself. Language operates sequentially in time: one word follows the next, building sentences that begin and end, telling stories or communicating thoughts that have a point, an end. Whereas collage offers a vision of pre-literate simultaneity and indeterminacy, writing is profoundly linear and determined. One can learn to overcome these factors of the written word, to an extent, but as a young writer I was constantly struggling to do that—or even to recognize that I needed to do that.

I think its good that I struggled as long as I did, as eventually it forced me to really learn the rigors of grammar and syntax, as well as the delicate interplay between these factors and a poem’s lines. After years of writing promising, intriguing poems that all felt stifled in some way by their awkward sense of form, I eventually got pretty good at writing rather straight, linear poems— I guess I needed to prove to myself that I could, but this was a rather hollow satisfaction. The real breakthrough for me occurred when I began to write in a more chaotic, collage-like style, using highly visual material, citations and fragments: moving linguistic objects around like cut-out pictures, while also bringing to bear my understanding of syntax. And this is when my first “mature” writing emerged: writing that others seemed to like, and which I also liked—what’s more, it was writing that excited me. In particular, the longish poem Dysnomia worked through a very overt collage technique, blending lines, fragments of syntax, and rhythmic pacing, with an assemblage of pieces form other sources. Just as I would cut out pictures from magazines to put on my bulletin boards, here I was sourcing documents to collage via syntax on the page:

Nevertheless, it was not until spring of 2024 that I finally threw myself into actual collage-making in a forceful way. I’m not entirely sure how it got started, but once it did, I found it difficult to stop. A local Half Price Books outlet, which sold used photography books with excellent prints for as little as $3, made it possible for me to build a large archive of images. And then I bought some ink, paint, and pastels to begin marking on them. I would start messing with a collage and then four or five hours would just evaporate (I was under-employed at the time, working part-time after having saved up some money from teaching a previous semester). It was exciting to get lost in all this, but I found it difficult to have any control over my days.

And its not like the end of those four hours, I always ended up with a beautiful collage I loved—not at all. Very frequently, the whole process was one of simply feeling lost, stumbling, searching for something and having no idea how to get there. A collage that begin focusing on a particular image would end up obliterating that image under several layers of scraps and pastel and paint, and I’d end up actively destroying things. A completely wrecked work would lay around for a few days, and then I’d pick it up again and find something in it and the end result would be amazing to me because it was the result of something I could never understand or control.

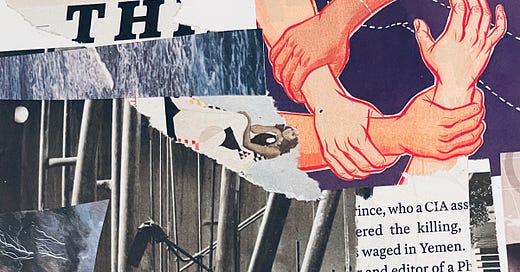

Here is one that bears evidence of total chaos:

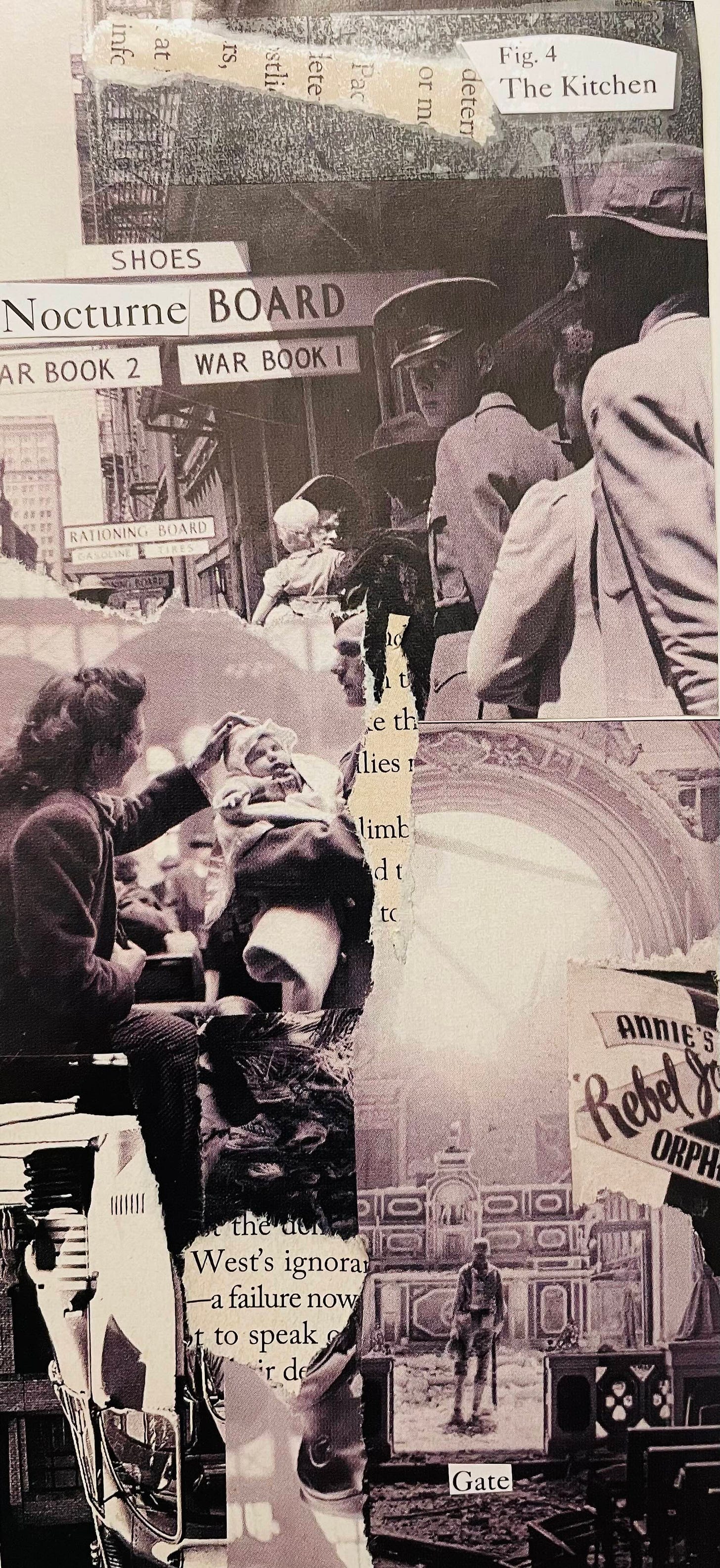

Here’s another that began as something very different, and then I began to somewhat destroy it and turn it into something else. Here’s the final version:

And here is where it began:

This process of continually evolving the work, even to the point of destruction, taught me a lot. You go into the work and understand that, although you can fuck things up, no fuck up is permanent: there is always something new to discover, and the discovery is what drives the whole thing—even the chase, the struggle. You do it to see how lost you can get and how you can still find a way into falling in love with it. And in doing this, you feel almost indistinguishable from the materials themselves, and yet you are not reducible to them—it’s a collaboration, or symbiosis. You totally give up intention here: what you “have in mind” means very little compared to what you and the materials stumble onto together. You look at physical, visual details—the eye tells you if you like what you see—and all the rest is up to the alchemy of the process: you are IN the collage.

And I can’t tell you how important this same understanding is to poetry: I had to at least encounter this same mentality in writing before I was ever able to write things that excited me. And without that excitement, I don’t see any reason to be involved with writing at all. If I’m not feeling excitement—genuine excitement, a sense of wonder—then how could I ever expect a reader to feel it?

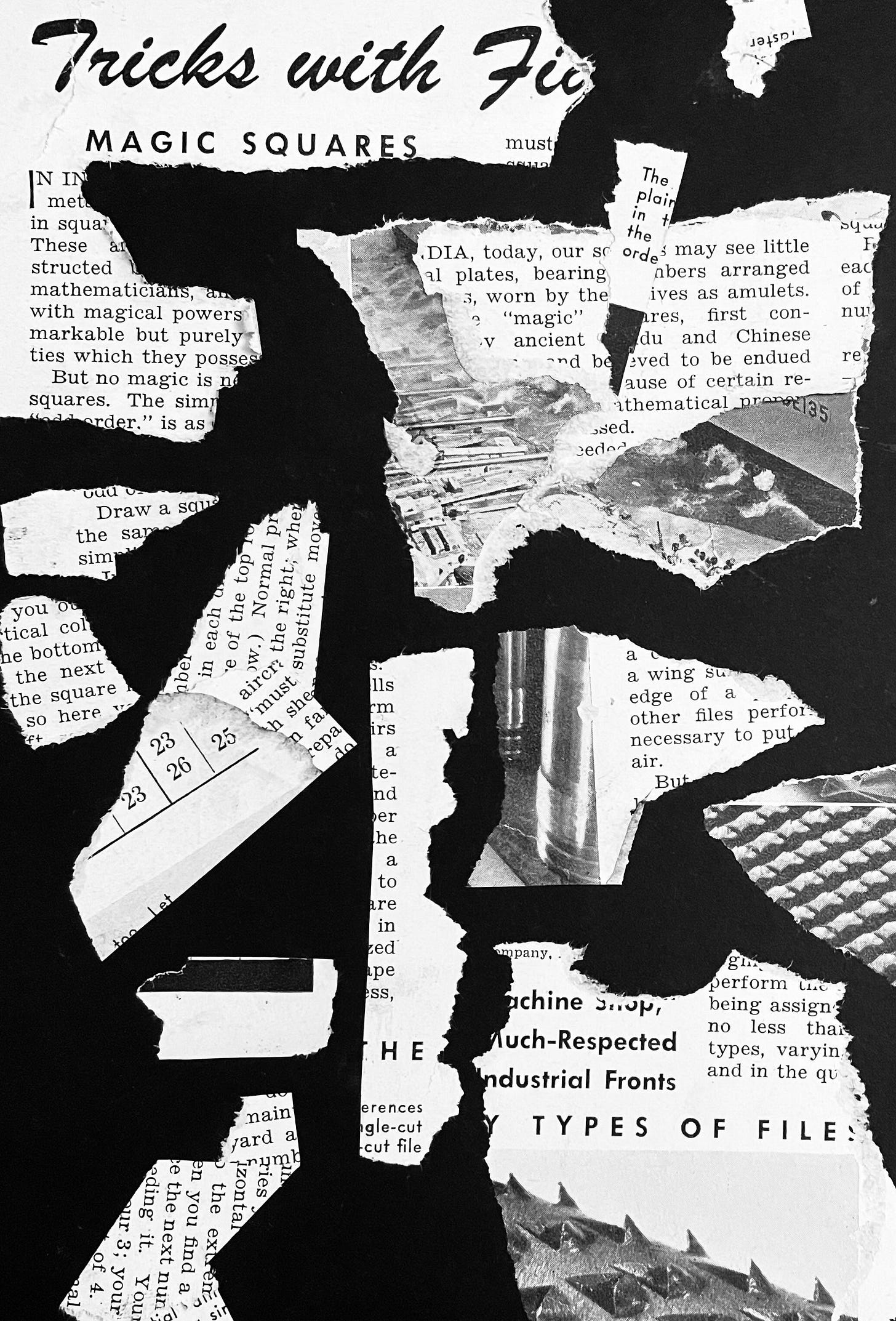

To close this out, here are a few of my other faves. These are a bit less immersive than the others, but I like them because they show a variety of approaches. They feel a bit more like sketches than the ones above, so no titles: