The Plot to Destroy Poetry?

Reflections on Publishing and the Idea of "Literary Exceptionalism"

“It does seem like a plot to keep people from reading poetry.”

— Bernadette Mayer in a 1979 interview w/Susan Howe

Modernists and Conglomerates

This essay is a companion to the poem excerpt I just posted. That poem is in dialogue with the work of Bernadette Mayer, and its opening lines make reference to James Laughlin, founder of New Directions books. Laughlin is a singular figure in American letters, and his role in the world we continue to publish within is significant. Laughlin was the heir to a steel fortune, and with that money he launched his press at the behest of none of other than Ezra Pound. ND published many of the most significant poets of the 20th century, and ND is still largely revered (and still in operation). Also, before his passing, Laughlin played a decisive role in the direction that small press publishing would take after him as well.

As Dan Sinykin and Edwin Roland argue in “Against Conglomeration: Nonprofit Literature and American Literature after 1980,” Laughlin helped champion the emergence of Graywolf as the torch bearer for a new non-profit model in independent literature in the 1980s. At the time, this was an adaptation to the conglomeration of big publishers, as the seemingly eternal names in publishing were being bought out by major corporations with massive stakes in the broader entertainment and media industries. Unable to win the fight to break up the conglomerates, many writers and publishers began to seek an adaptation, asking, “What if, like dance, opera, and orchestras, literary books could be subsidized by state-sponsored grant funding and private philanthropy?” (Sinykin and Roland). And this is the way things went: this is the world we are very much still living within.

For many writers, especially those coming through the MFA system, this is treated simply as a natural state of affairs. No matter how many writers know that reading fees are onerous, contests are a scam, and big literary orgs are nearly always on the wrong side politically, there is still little understanding of how this all works economically. As Sinykin and Roland discuss, the non-profit model of arts funding, ostensibly freed from the market, shaped literary production in a specific way. In a sense, being “freed from the market” made it possible for the ruling class to manage literary culture and production in insidious ways:

State money and philanthropic money come with expectations. As nonprofits published writing that the conglomerates deemed unfit for the market, they chose and shaped that writing according to their own financial needs. What priorities would funders, explicitly or not, want to see expressed in the literature they financed? What would have success in nonprofits' smaller but still consequential markets? What values, aesthetic and otherwise, were encoded in the missions of government units and foundations that could guide the editorial practices of the nonprofits? Despite the cant of liberation, markets still mattered to nonprofits: their innovation came from balancing market success with other priorities. (Sinykin and Roland)

In time, this non-profit model and its further adjustments have had the effect of centralizing the relatively meager funding for literature in this country to a few marquee presses and organizations. It has led to a situation in which the professionalized presses and journals compete to be named as partners with Amazon; Wells-Fargo and Target logos appear in the inside of Graywolf books; and Ballard-Spahr, a (union-busting) law firm, sponsored a lucrative prize through partnership with Milkweed Editions. For individuals, no one lacking credentials and connections is going to have access, and those operating in more egalitarian DIY spaces sometimes see this as a mere stepping-stone to their future career successes. And this only barely begins to scratch the surface of the complicity in literary culture.

A Definitely Paranoid Feeling

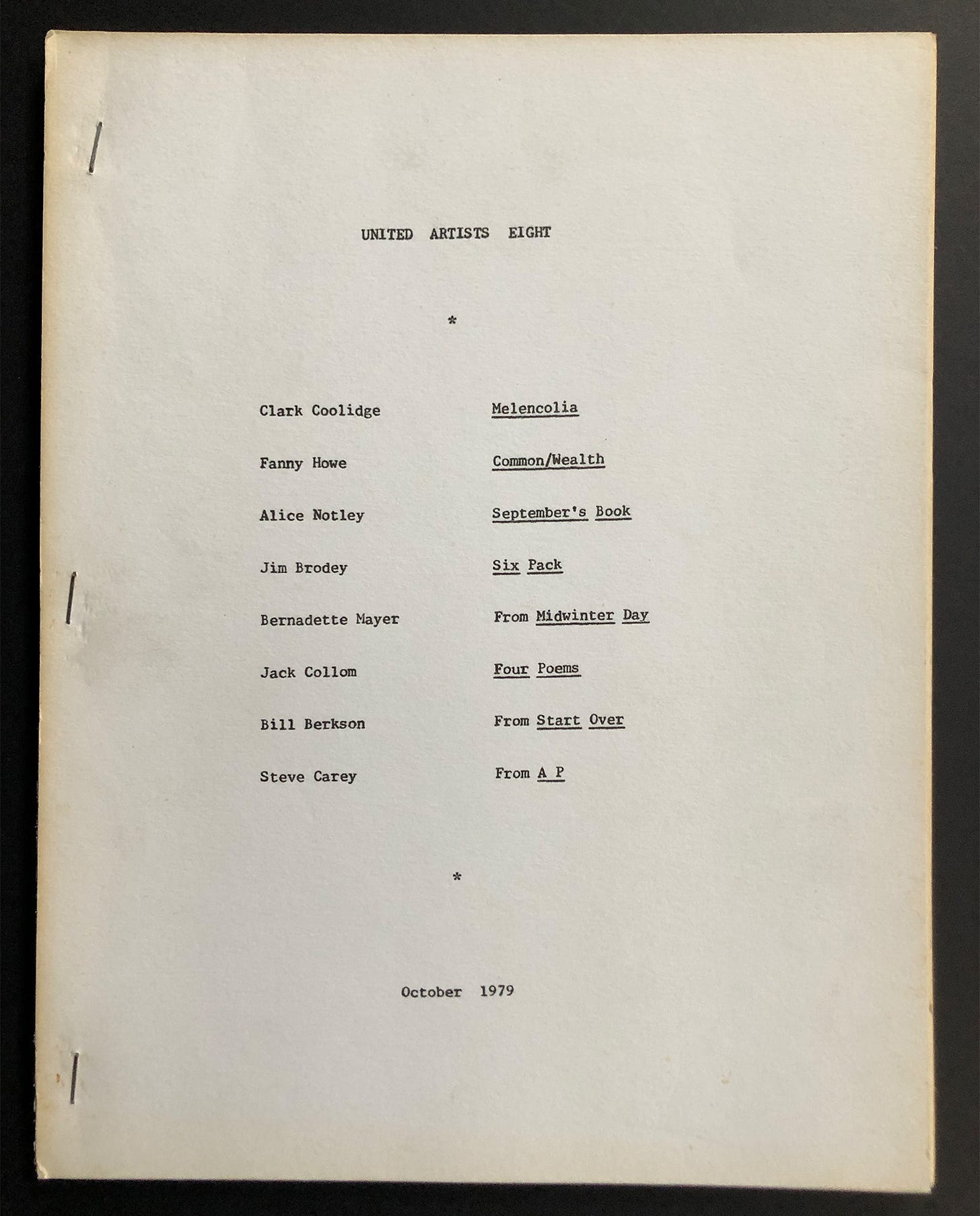

Interestingly, the problem of conglomeration and its consequences for small presses is directly addressed by Mayer in a 1979 interview with Susan Howe. That year would have been seismic for people attuned to the shifting ground within publishing: conglomeration was in full swing, and neoliberal policies were about to clamp down on arts funding. Mayer appears highly conscious of all of this as it is happening to her and her friends, and she is speaking from within the blurry moment of knowing something is going on but not knowing where it is headed or who is steering .

One of her most acute statements on this moment occurs out of a discussion about self-publishing. Mayer begins by championing this DIY approach, and then she goes on to address some of the paranoia that writers were feeling in this era, right as conglomeration and changes in NEA funding were beginning to take hold. In this passage, Howe has asked Mayer directly why she prefers self-publishing:

Mayer: Well, why not? Nobody else is going to publish it! [Laughs.] I think it’s great to publish one’s own work. I never felt any vacillating about that whole thing. The first book of mine that was ever published, which was this book called Story, I published myself. It seems like a way to disseminate writing in a very efficient way. You can get it to all the people who you know are going to read it. There’s no fooling around. You can do it the way you want it done. Nobody ever tells you: change this or that, or I’m going to put this cover on your book. It’s all in your own hands. . . . I know that none of us as poets are ever going to be published by the so-called publishing companies, because ultimately the government has written us out, haven’t they? It seems that way. It seems John Ashbery and James Schuyler are probably the last great poets to have contracts with real publishing companies.

Howe: You think that’s true?

Mayer: I don’t know. I’ve talked to a lot of people about it and nobody seems to know the answer. Some people have a definitely paranoid feeling that that’s the reason that small presses can get publishing grants now from the government rather easily, I mean, if they’re devoted to it, to some extent it’s because it’s an accommodation to that situation where none of the publishing companies are even acting independently really anymore. So they won’t publish poetry because they’re all owned by the entertainment conglomerates. It does seem like a plot to keep people from reading poetry. And I know that a lot of poetry by me and by Ted Berrigan and by Lewis and by Alice [Notley] could be read by a much wider audience. That’s how it stands, and it’s so intractable. If we’re going to continue, and to continue to publish at all, then these are the terms we seem to have to do it on. I don’t mind it, except in the sense that I wonder if people are being cheated out of reading more poetry, because certainly whenever a book of poetry does get published, it doesn’t ever get any kind of publicity or advertising or anything like that. Nobody ever reviews it in The New York Times. We publish books now in editions of 1,000 copies. That seems to be about as many as can be distributed, and that’s not too many. (Howe and Mayer; my emphasis)

Admittedly, some good things have happened to poetry since this time, such that getting a review in the NYT is not quite so unheard of (if you count that “good”). And certainly, some major publishers do run new books of poetry. There is a more organized network available to poets who want to learn more about the art form, and there are numerous sources of funding available. In theory, all of this is “progress” for the “field of poetry,” but one thing is clear: the real benefits of these changes accrue to the few, and very rarely to those who could benefit from them the most. Need-based funding for writers is rarely offered. But when funds from the state and from donors are heavily merit-based, when merit derives from academic and professional success, and when success on these terms is more demanding and precarious for racialized and marginalized communities (and those who do not come from wealth or an academic background), then resources are regularly directed to those who already have them: success begets more success, and the rest can go broke.

Refusing Literary Exceptionalism

If a plot to keep people from reading poetry may seem paranoid of Mayer and her fellow writers, it’s not that far off from what we ultimately got: a plot to sever essential funds from those writers and publishers deemed “unprofessional.” If nothing else, the new system that has taken hold since 1979 is highly professionalized, upheld by a system of credentialing (MFA), certification for non-profit status, competition for lucrative grants and awards, and dependence on wealthy donors and corporations—to say nothing of the way that gentrification and out-of-control rents in NYC and other metropolitan centers has completely transformed the cultural landscape. In short, the presses and poets who appear in these spotlights, and who receive the bulk of the available funding and resources, are usually operating in a milieu that has been completely transformed by professionalization and all that comes with that.

Of course, the real crisis here is capitalism, the system through which conglomeration became inevitable. It was the conglomerates who made publishing impossible for all the rest, much as Amazon is driving booksellers out of business today. The non-profit model is an adaptation to this crisis, not its cause, and that is important to bear in mind. However, over the years, this adaptation has made it all too easy for literary producers to trumpet the supposedly progressive nature of their enterprise, as though “non-profit” equated with morally righteous, or that it may even mean “anti-capitalist” (who knows?!). This leads to a position of absurd rationalization and obliviousness regarding the economics of small press production and how it fits into larger structures. Thus, while the non-profit adaptation did not cause this problem, necessarily, it has become a problem here in the 21st century. And this is because it has instilled an ideology I call literary exceptionalism: the belief that literature is a calling, a practice that is essential both to humanity and democracy, and that it is immune from economic critique. In other words, “Don’t ask questions about Amazon giving us money. We’re doing the good work, and that is all that matters.”

I’ll return to this line of thought in future posts, but that is all for now. There is much more to say, but if I tried to say it all, I’d never finish this post. For those interested, much more on all of these matters can be read on the Poets Union’s Reading Room. I’ve also written about these things myself here and here.

I always appreciate your thoughtful essays. Especially this one. Thank you for sharing!