"Another Dream, Another Dollar"

On John Cassavetes, money, and the spirit of Cosmo Vitelli

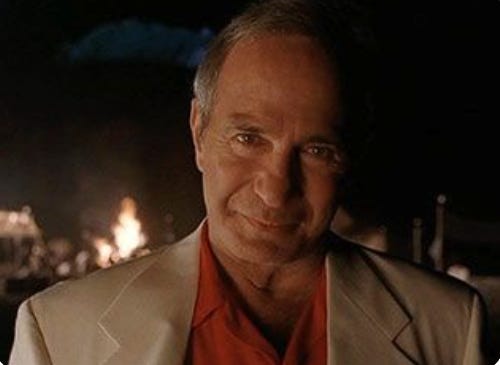

John Cassavetes’ The Killing of a Chinese Bookie was first released in 19761. It tells the story of Cosmo Vitelli, a beleaguered club owner, who is forced to carry out a killing to erase his massive gambling debt. However, this basic premise tells next to nothing about its essence. It is a film filled with delays, digressions, and stray moments that accumulate into a profound character study of Vitelli. And so much of this depends upon the inimitable quality of actor Ben Gazzara’s face. In fact, it is nearly impossible to imagine any face but Gazzara’s for Vitelli. His high forehead, enhanced by receding hairline, extends down his long nose in one powerful line, suggesting someone who glides forcefully into place. The face is lovable and comic yet elusive, mingling bravado, menace, and deep cynicism with signs of defeat, sorrow, and an almost gentle politeness—at times, all of these happen in the same moment.

This face is a vivid index to Vitelli’s resilient but baffled personality. In it, we see all of his facets: the (pseduo-) sophisticated, smiling patron welcoming his guests and hyping up the next routine; the frustrated, small business owner who struggles to hold it together; the petulant, demanding poker player who loses all perspective and throws away tens of thousands in a night; the cornered mark whose features are wracked with disgust and confusion, as though incredulous at the script his fate asks him to play; someone who “may be dumb but [is] nobody’s fool”; and a war veteran who carries a .45 into a stranger’s house, finds him naked in his room, and kills him. Ultimately, the face tells the story of what it has cost him to preserve his life’s fundamental dream: running the Crazy Horse West, a strip club in Hollywood.

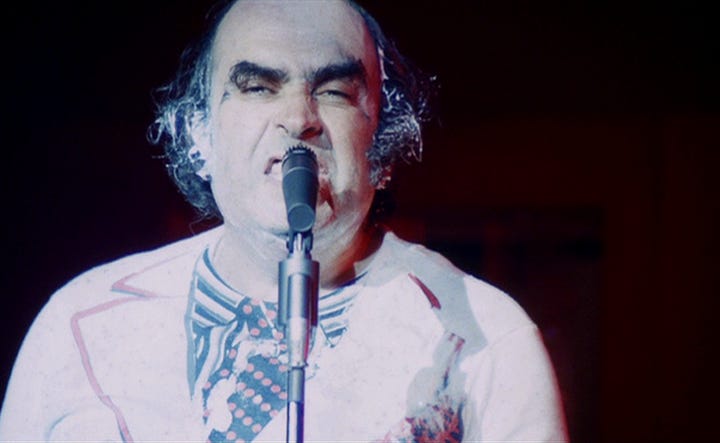

For Vitelli, everything revolves around the Crazy Horse. He is fully committed to its reality, seemingly worrying at all times about making sure it lives up to his belief in it. Even while bleeding, with a bullet lodged in his side, his ultimate priority is to keep the club’s stage show going—and the show is not what one would expect. Most of the time, no one is even stripping; instead, characters are grossly costumed, trotting out ridiculous props in some kind of Dadaist burlesque, trying to recreate Paris or the OK Corral. The slightly freakish singer and emcee Teddy (aka Mr. Sophistication) repeatedly speaks and sings of love, and of imagination and its powers, while many in the crowd are waiting only for topless women. But this is how Vitelli wants things. He is proud of what he’s created there and lets the crowd know, “I own this joint. I choose all the numbers. I direct them, I arrange them. And if you have any complaints, you can come see me, and I’ll kick you right out on your ass.” Yes, Vitelli runs a strip club, but it’s also his canvas. He is, in his way, an artist.

A Basic Disrespect for Money

It’s well known that John Cassavetes saw himself in Vitelli. The fact is commented on by both producer Al Ruban and Ben Gazzara himself. Like Cassavetes, who was known to work with the same close-knit group of actors in almost communal environments, Vitelli has constructed a family of intimates who share a world together in the Crazy Horse West nightclub. We get to meet Teddy, Sherry, Derna, Sonny, Carol, and several others in Cosmo’s (ahem) cosmos. Just as Cassavetes’ wife, Gena Rowlands, was the lead actress in multiple of his films, so too is Vitelli dating his own club’s star, Rachel. But for both men, perhaps the most crucial similarity is their financial struggle to keep the dream world alive.

In Bookie, money is simultaneously total bullshit and a force with the power of death. The plot twists around two facts of Vitelli’s finances: first, we see him pay off an enormous debt on his club after seven years of humiliating visits from a loan shark; secondly, we see him lose the club all over again and go $23k in the hole while celebrating paying off the seven year debt. It is a ludicrous, brutal turn of events that leaves Vitelli in the hands of men who value neither his club nor his life. Now Vitelli, who choreographs and directs the routines in his club, has to act out the lethal and soul-destroying routines scripted by gangsters.

This is a bind Cassavetes understood all too well. In the book Cassavetes on Cassavetes, editor Ray Carney writes, “The gangsters [in Bookie] are [movie] producers (right down to their obsession with contracts), and Cosmo is every filmmaker who agrees to adhere to someone else’s script and ‘shoot’ something he doesn’t really believe in in order to clear a debt.” Similarly, to Gazzara, Cassavetes explained his character’s motivations — supposedly while in tears — by conflating the producer and the gangster:

Ben, do you know who those gangsters are? They’re all those people who keep you and me from our dreams. The Suits who stop the artist from doing what he wants to do. The petty people who eat at you. You just want to be left alone with your art. And then there’s all the bullshit that comes in, all these nuisances. Why does it have to be like that? (qtd. in Carney)

Cassavetes had an almost visceral disdain for producers and executives and all those who controlled the means of film production. And yet, according to Carney, he also consciously saw Bookie as a more commercial production in its concessions to 1) the genre of the gangster film, and 2) the presence of nudity — both factors known to draw bigger audiences. Like Vitelli, Cassavetes is trying to realize his dream while understanding that this is only possible through selling some part of himself.

Everything costs. For the independent filmmaker of Cassavetes’ era, moving among the various sharks meant risking self-betrayal and artistic failure, and it almost guaranteed a lifetime of debts and losses. It took extraordinary courage to throw oneself into this, and, perhaps more than that, it took a lot of gambling. As Cassavetes stated in an interview, “Making a film is extremely expensive. The only way you can make one is by having a basic disrespect for money.” And without doubt, a basic disrespect for money is apparent throughout Cassavetes’ life. Truly no perfectly rational person would have made films the way he did. Like Vitelli, Cassavetes was crazy in a world where money is sane. He was a gambler in everything he did, and so it is fitting that his protagonist/surrogate goes from paying off a debt of seven years to gambling himself $23k in the hole in less than a day. As Vitelli says, “It’s all paper.” It means nothing to those who have tons of it, why should it matter to me? Of course, for Vitelli the risk was much more serious than he let on, and in the end, his mortality was the only collateral he had left.

In the Mirror of Jackie Treehorn

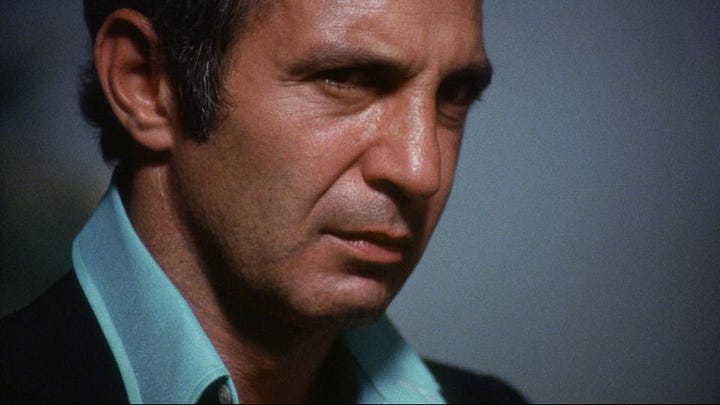

We don’t know exactly what happens to Vitelli after the credits roll. We last see him on the sidewalk before his club, dripping blood with a bullet in his side. However, we do know that his face, Ben Gazzara’s, forcefully reappears twenty years later in The Big Lebowski (1998). The face’s entrance in the film could not be more dramatically framed. He approaches in slow motion, eyes fixed directly on the camera, and then says his own name aloud, as though greeting the audience. Although his role in the film is small, it is powerfully emphasized, and I have no doubt the Coen Brothers’ are nodding throughout to Cosmo Vitelli.

There are numerous surface details one can point out to draw the connection. For example: both Treehorn and Vitelli are in adult entertainment; the indoor pool in Treehorn’s inner sanctum calls to mind the dramatically central indoor pool of the mob boss Vitelli is sent to murder; Vitelli and Treehorn both denigrate someone as an “amateur” (with a hard T); and characters in both films ignorantly refer to a man named Wu as “the Chinaman” (“not the preferred nomenclature,” as Walter Sobchak reminds us in Lebowski).2 However, these coincidences are less essential than the more basic commonality between the two films: they are both highly idiosyncratic LA noirs about the nature of masculinity in which a down-and-out guy gets set up by rich assholes to fail in a caper, and against all odds both men succeed by, essentially, failing. They are stories about underdogs whose oddly constructed social worlds are invaded and nearly destroyed by wealthy, ruthless assholes.

However, in Lebowski, Gazzara’s role both echoes and reverses the character of Cosmo Vitelli. At first, Jackie Treehorn seems to be a version of Vitelli if he were financially successful. He is relaxed and living in luxury, sharing Cosmo’s taste for “sophistication” and enjoyment of life. The scene in which he first appears shows him hosting a party on his beachfront property unlike anything Cosmo could afford, but it is in keeping with the latter’s beloved role of host and provider of good times. Treehorn’s whole demeanor exudes the stylized “sophistication” that Cosmo was so desperate to portray. However, it soon becomes clear that this doppelgänger is a kind of betrayal: he is a cynical businessman and loan shark willing to claim what’s his through violence. In fact, Treehorn is one of those very sharks Cassavetes and Vitelli so loathed, someone destroying the dream of those whose “basic disrespect for money” is matched only by a love of people and imagination. Whereas Bookie asks the audience whether or not Vitelli would truly be capable of cold-bloodedly killing a man who’d done him no harm, Treehorn shows us what would happen if that cold-bloodedness moved in and took over his whole personality, turning him into his own enemy.3

Ultimately, it is the Dude, played by Jeff Bridges, who comes closest to the spirit of Vitelli in The Big Lebowski. Admittedly, the two films and their protagonists could hardly be more different. Lebowski is ultimately a feel-good comedy, a buddy movie, while Bookie is torqued, existential, and unnerving. And the Dude lacks all of Vitelli’s pretensions to sophistication, taste, and class. And yet the Dude and Vitelli are aligned in a much more important way: they are both living outside of the social norms enabled by wealth, good credit, and respectable employment.4 They are, in the Dude’s words, both people “the straight world doesn’t give a shit about.” In the eyes of the wealthy and powerful, they are simply expendable quantities. After all, despite the comedy of the larger scenario, the suitcase ringer given to the Dude by the elder Jeffrey Lebowski was intended to get him killed. Like Vitelli, the Dude is little more than a pawn — or, more precisely, a coin for someone else to spend.

However, both Vitelli and the Dude have found a way to exist in a different sort of social economy — a kind of underground in which they have entire eccentric worlds of their own where they know that they belong. In their makeshift families — lacking property, children, or legitimate professions — they pass the time and process the confusions and threats of a world outside that is at once hostile and boring. Whereas Vitelli has his family at the Crazy Horse, the Dude’s family is with Walter and Donny and the bowling league, a pastime to which he — like Vitelli with his choreographed burlesque routines — fully commits his energies. Both men pursue their economically bereft realities despite the fact that they may appear to others as unappealing, ridiculous, and dysfunctional.

“Imagination makes you crazy”

Many struggle with Bookie because Vitelli’s stage show is bizarre and objectively bad. In fact, the original 1976 version was edited and re-released in 1978 with many of these stage scenes removed. It is difficult for some to know how to take Cosmo’s own approval of these performances. And even Cosmo himself sometimes seems baffled at what he’s doing: “What kind of strip club is this? No one takes off their clothes!,” he exclaims at one point. But that is just it: the stage show at the Crazy Horse West is a place where you can simply be crazy and it’s OK. You can do things you don’t understand, get lost in fantasies that go nowhere, or that end up meaning things you could have never planned for. As Teddy’s song tells us, “Imagination is crazy / your whole perspective gets hazy . . . / Imagination is silly / You go around willy-nilly.” And that’s good. Because without it, life is worth nothing. It’s only paper.

Admittedly, because I am reading Cassavetes through him, I run the risk here of idealizing or sentimentalizing my account of Vitelli. And yet, despite the film being a noir in which the protagonist kills a defenseless man in cold blood, Cassavetes has made it so that idealism and its contradictions are at the film’s core. In essence, Cosmo was a man who couldn’t figure out how to make his dream real in the world he existed in. Dressed lavishly and chauffeured around in a limo, surrounded by his De-Lovelies, he projects the fantasy of the thriving small business owner. But the fact is that at no point in the film does he actually own the Crazy Horse. At any point, loan sharks were ready to foreclose on him, and eventually they do. And ironically, despite his likely dying for it, it seems he truly did not want to own a small business — at least not in the limiting, conventional way. Buried in the tawdriness and financial scheming of it all, Vitelli is fundamentally trying to build a free, communal reality — a utopia. And the contradiction of trying to do that with capital is one that finally destroys him.

Ultimately, the Crazy Horse is a precarious oasis of play and creation in a society where reality is bought and sold, where individuals are broken down and compromised by fate, violence, and debt. Yes, the Crazy Horse show is ramshackle and pitiful, but it is also an instance of human beings coming together to keep their hearts and minds from being destroyed by their need to pay the rent. And in case it is unclear what Vitelli was really trying to keep alive, just consider the songs he chose: “Imagination,”5 “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love,” and “Love (Not War) Rules the World.” Vitelli himself is deeply sentimental, but he is also baffled by his own sentimentality. He intuits, somehow, that dreams are not about “success” and “making it big,” but about doing something that transforms us. Dreams are how we see beyond the degraded realism of capital: they can become collective acts of world creation, of mental autonomy and free association, a world-transforming social nucleus. And yes, he is comical and brutal, and yes he fails, but he is also an avatar of some of Cassavetes’ profoundest artistic impulses. For where one person might see — on the Crazy Horse West stage, or in one of Cassavetes’ pictures — only chaos and insane improvisation, others may see life-saving evidence that the socially liberating power of imagination has not yet been destroyed.

*

Coda

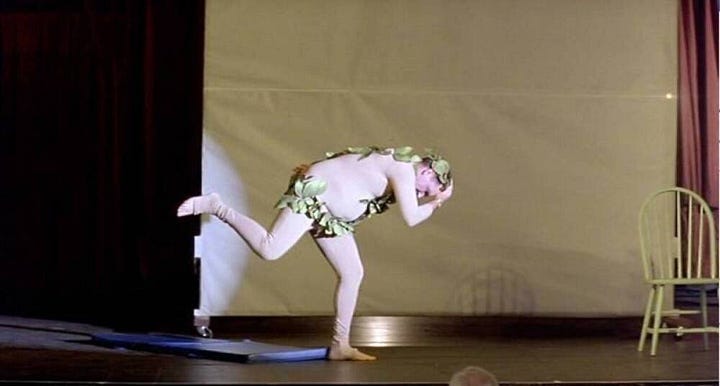

In one of the strangest scenes in Lebowski, the Dude gathers with friends Walter and Donny in a theater. The three men watch as the Dude’s eccentric landlord, Marty, performs a “dance cycle” on a stage with nothing more than a spotlit screen, a floor mat, and a chair. Wearing a spandex suit and fake laurels, the out of shape man plods his way through his own bizarre choreography. It’s one of the most absurd moments in a largely absurdist movie, and it is almost impossible to truly dignify it. Still, I can’t help seeing it in light of the Crazy Horse West’s surreal stage show and the spirit of Cosmo Vitelli. That is, even tho I laugh and can’t imagine being in that audience, I feel that true generosity is being shown here by the Dude. After all, not only does he attend this absurdity and watch patiently, but he brings two friends.

Of course, it’s likely he’s just trying to keep Marty off his back so he doesn’t get evicted, as we know the Dude’s rent is overdue. But does this really change things that much? Sure, he can’t give the money he owes, but he can give him the basic dignity of his attention and show interest in this act of imagination. And amazingly, that seems to be enough for now: Marty lets him continue living there, unpaid. The whole dance scene is fleeting, and it’s ludicrous, but it’s also a moment of in which we see that even this guy who profits off of rent has a dream that he’s desperate to realize: he wants something profit can’t provide, and he’s willing to become ridiculous to try to find it and make it real. And in the spirit of Cassavetes and Vitelli, however slightly, the Dude recognizes that and gives it his time.

In 1978, Cassavetes re-edited the film, and the ‘78 version has been taken as definitive ever since. Interestingly, in 1977, between these two edits, Cassavetes made Opening Night, which featured Gazzara as a successful stage director of serious drama. It offers a fascinating parallel with the comical anarchy of Vitelli’s own stage productions, and there is absolutely another essay to be written about how Opening Night fits into the Vitelli legacy I am outlining here.

While there is a discussion to be had about Orientalist themes in Bookie, it’s worth noting that the eventual portrayal of Wu in Bookie’s murder scene humanizes him in a shockingly intimate way, totally destroying any stereotype one might have had of an Asian-American crime lord. That this also would have been a major disappointment to mainstream American audiences then fascinated with the martial arts and Orientalist tropes further reinforces Cassavetes’ refusal to deal in stereotype. Nevertheless, he himself understood this to be part of his compromising concessions to the box office, just like the film’s use of gangster tropes and nudity: he even allowed the font in the title sequence to have a vaguely Chinese appearance. However, he was so conflicted about it — putting everything else in the film at cross purposes to these surface compromises — that the audience perceives no concession whatsoever, and to them the title’s promise of an Orientalist gangster film was little more than a disappointing ruse.

One also has to wonder what Vitelli, the would-be sophisticate and auteur, would have made of Treehorn’s own video production, Logjammin’.

Just as the Chief of Police of Malibu discovers that the Dude carries nothing besides a Ralph’s card, the gangsters who move in on Vitelli find he has nothing but a “gold gas card.”

This song gives my essay its title. Teddy/Mr. Sophistication introduces it with an ad-libbed quasi-poem that includes the lines, “Another dream, / another dollar, / imagination.”