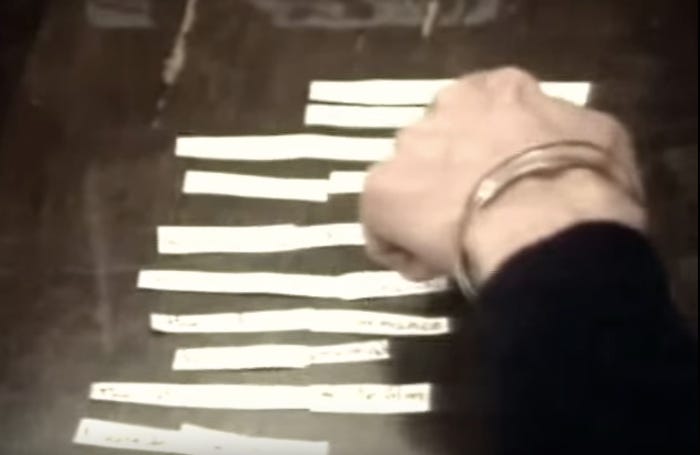

I’ve often messed around with cut-ups, and I’ve been aware of this method since I was probably 15 and reading about William Burroughs. He had adopted the idea from Tristan Tzara1, and while it was often considered a parlor trick, Burroughs used it with an intensity of vision that hadn’t been seen before.

The thing about cut-ups is that they have source ma…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Out of Its Wooden Brain to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.