FRANCES FARMER WILL HAVE HER REVENGE ON THE COMMODITY FORM (part 2)

On Nirvana, Capitalism, and the History of Underground Music

What follows is part two of an essay I posted last week. This one completes the history that broke off last time around August 1991, on the brink of Nirvana’s fame. In addition to filling out the rest of the history, this essay also extends into the present to think a bit about how our ideas of independent culture—counterculture, underground, what have you—are understood today.

I hope you enjoy it. And if you do, please share it wherever you can <3

OUR LITTLE GROUP HAS ALWAYS BEEN

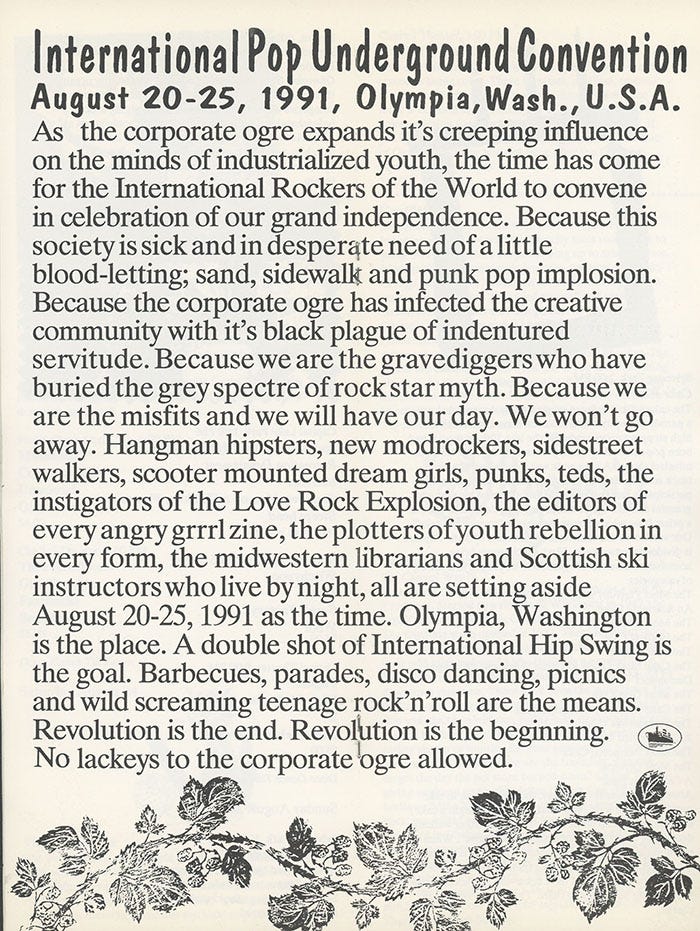

The pivotal fall of 1991 saw not just the collapse of the USSR and the release of Nevermind. It also saw the International Pop Underground Convention (IPUC) in Olympia. The convention was organized by Calvin Johnson and and Candice Pederson of K Records, and the result was a unique music festival where, according to Tobi Vail, “It seemed like everyone here was in a band and it was just like people in the audience getting up on stage and vice versa.” In addition to first-time performers, the IPUC included acts like Fugazi, Beat Happening, Bikini Kill, Unwound, Built to Spill, Melvins, L7, Bratmobile, and 7 Year Bitch. It was a celebration that united much of the underground, drawing bands from across the US and even some from Europe (e.g. The Pastels). And yet, as Azerrad writes in Our Band Could Be Your Life,

”this celebration was also the end of an era for the indie underground.” According to Fugazi’s Brendan Canty, “[I]t didn’t necessarily feel like it was going anywhere or that we were using it as a launching pad for the Nineties” (qtd. in Azerrad). The question that resonated seemingly everywhere else sounded here too: Where was all this going?

Within mere weeks of the festival, Nirvana would emerge as a defining band of the nineties, but they were conspicuously absent from the ticket at IPUC. Although it happened in their one-time home of Olympia, and although Nirvana did contribute a song to a Kill Rock Stars compilation that in many ways defined the festival, there was a sense that they’d been excluded. The very manifesto/announcement of the festival—written by Calvin Johnson—insisted on a drawing a line that antagonized the band:

As the corporate ogre expands its creeping influence on the minds of industrialized youth, the time has come for the International Rockers of the World to convene in celebration of our grand independence. . . Because the corporate ogre has infected the creative community with its black plague of indentured servitude. Because we are the gravediggers who have buried the grey spectre of rock star myth. . . . Revolution is the end. Revolution is the beginning. No lackeys to the corporate ogre allowed.

There is nothing egregious here, but for a band newly signed to a corporately owned major label, the message was unmistakable. Here, the revolutionary stance and rhetoric that Kurt had internalized was being deployed against him in a very public way: far from recognizing the legitimacy of his crusade, he had instead been reduced to “lackey.” In her memoir, Kathleen Hanna writes, “[T]he repetitive mentions of its being ‘anti–corporate rock’ seemed pointed at Nirvana, since they’d just signed to a major label and left Olympia. It felt like a line was being drawn in the sand: Nirvana was no longer welcome in K’s indie purist clubhouse.”1

Still, despite the rhetoric, it's not entirely clear why Nirvana did not appear, as by all accounts, they wanted to play2. In one version of events, the band was told NO—both indirectly in the manifesto, and directly via conversation—while in another they were prevented from playing due to a scheduling conflict: they had already agreed to play the Reading Festival while touring the UK with Sonic Youth, which happened the same week. Regardless of exactly how it occurred, Nirvana insider Everett True insists there very much was a falling out with Olympia. As True puts it, “That casting out from Olympia, whether it was deliberate or not, it did happen.” As friend and confidant of both Kurt and Courtney Love, True claims that Kurt spoke repeatedly of a phone call he’d had with Calvin about his appearing on the bill, and it seems to have stuck with Kurt and hurt him. And as seen in Kurt’s journal entries, Calvin became a target of increasing ire after Nirvana became famous—he would not let it go.

Without delving too far into psychology, it’s worth noting that, despite his irreverent pose, Kurt badly wanted love and acceptance—more specifically, he was torn between wanting to be free and wanting to belong. In this fall out over the IPUC, Kurt seems to have felt rejected and judged by people he admired and sought acceptance from, and from a world he wanted to belong to, and these feelings hardened into a complex fixated on betrayal. That this would occur in the fall of 1991, just as he was about to break through into world fame, is a significant thing, but it is not an isolated case. Over the remaining few years of his life, new sources of betrayal would emerge, and these feelings would worsen with terrifying speed.

Of course, we all know where the story is going. And when viewed in retrospect, as a tragedy, Kurt’s story can begin to seem inevitable, as though fame and a violent ending were somehow essential to what Kurt was. But the history he was living and making is not identical to the story we tell in retrospect. In 1991, Nirvana was living a narrative that, to them, was a hopeful, youthful one, opening into the indeterminate space of the future3—it could have gone in any number of directions. The only real inevitability here is that, when one’s narrative is hijacked and rewritten by the marketplace, it’s not going to go your way any longer. With fame, whatever revolutionary currents ran through them became subject to the tyranny of an industry.

NOTHING ON THE TOP BUT A BUCKET AND A MOP

Up to August 1991, everything had been going according to plan: the band had signed a deal, recorded a record, toured Europe with Sonic Youth, played the Reading Festival, and readied its first video. These were normal, by-the-book decisions that could have led to moderate outcomes. Yes, Kurt understood the friction generated by a stale musical culture and a musical underground that was growing in vitality, and he saw the potential to exploit it—both for himself and, idealistically, on behalf of the underground. And yes, he was highly sensitive to the timing of their historical moment. But neither he nor his record label, nor any other person alive, anticipated just how big Nevermind was going to become. In retrospect, we see it tied in with a zeitgeist, as though all this were a matter of course. But in the moment, for the band, it was a freak event: something wild and exhilarating and full of possibility—but also something ludicrous, bizarre, mind-numbing, and terrifying.

A cynic—someone such as Kurt himself—may have looked at this situation and said, “Well, you signed the contract, didn’t you? I guess you should be more careful what you ask for.” But the fact is that that signature was little more than a modest bet. By most accounts, it seems that everyone involved was aiming for moderate success: a gold record (500k sales). That was well within the realm of possibility, although it would mean outselling Sonic Youth’s major label debut, Goo (200k copies). Such a feat would have secured them financially and slightly raised their profile but without fundamentally changing what they had been doing. And for its part, DGC was committed to this, although they had assumed it would take a while to reach this mark: in fall of 1991, the label shipped a mere 45k copies to stores across the country—quite low expectations. Then in September, “Smells Like Teen Spirit” hit radio and MTV, and the band was struck by a commercial lightning bolt. By early 1992, less than six months after its release, Nevermind had well-surpassed gold record status and was selling 300k per week. It became the number one Billboard album twice, and by the end of its first year had sold over 4 million copies. For this band, and for the culture it had come from, this was absolute insanity. It realigned everything in their lives.

At this point, Nirvana’s world took on the quality of a grotesque cartoon, almost a parody of success. Often, the band leaned into the surreality of the public spectacle, but mockery can only go so far. Now that they had become a source of massive corporate revenue, they had to factor in numerous interests, often competing ones, from among their professional contacts and representatives. Not only their own team, but the entire music industry—concert venues, radio stations, MTV, magazines, etc—had begun to see them as a source of profit and clout: they had become a serious commodity. In a revealing journal entry from shortly after the band’s success, we can see Kurt’s dawning awareness of this new dynamic, where he writes in seeming disbelief of having become “a tenant of the corporate landlord’s regime” (you can hear the uneasy rhyme here with Calvin’s “lackey to the corporate ogre”). Where Kurt had thought the band could simply “stay in [their] own little world” while taking advantage of the major label’s distribution, publicists, and money, they found instead they had to really “play the corporate game” because they sold “ten times” more records than they expected. Quite simply, they’d made too many people too much money—a bad idea if you want autonomy. In the words of Krist Novoselic, things changed almost immediately: “There was no longer a sense of freedom—that was gone. Everything after that was a sense of disconnection and burden and crisis. We never recaptured that freedom because there were all these obligations. It seemed like our destiny wasn’t in our hands anymore” (Cross, “Requiem”).

Earlier, Kurt had dreamed of “sabotaging the empire from within”—of smuggling radical ideas into mainstream culture. By 1992, they realized whatever subversion they might be able to achieve would also mean being a kind of puppet—a rock and roll marionette. They wanted a revolution, but they had become too big to lead it with any real autonomy. Yes, the band took a meaningful stand: they spoke out in interviews about rape, sexism, homophobia, and racism, and played concerts advocating for the gay community in Oregon4 and for victims of sexual violence in Bosnia-Herzegovina; they appeared on AIDS awareness compilation No Alternative; they actively supported numerous small, underground bands and boosted sales for artists who badly needed the income; and they arguably pushed the limits of censorship. But as we know from various accounts, the demands from media, promoters, and others often pushed them into compromises through borderline coercion: Do this tour or we won’t promote your next record. Play this festival, or we will refuse to work with any other band in your management company, hurting the careers of people close to you. Play our awards show, or we will stop running your videos—we will even punish bands you like with the same treatment.5 This was what it meant to “serve the servants”: when serving an endless series of exchanges and performances and compromises and decisions, the only king is capital.

Kurt possessed extraordinary vision, resilience, and drive, but he was also overwhelmed by the conflicting pressures around him—it was ugly and relentless. As Kurt succinctly put it to Everett True, “So all the political nastiness that I’ve heard of for years from independent record people is true” (428). Elsewhere, he said to True, “There are just so many things that I’m not capable of explaining in detail . . .People have no idea of what is going on . . . The sickening politics that are involved with being a successful, commercial rock band are real aggravating. No one has any idea” (432). Despite his complaints, and in a testament to his underlying sweetness, Kurt actually did all he could to please everyone: fans, fellow bands, managers, MTV, his label, his family—and it absolutely burned him out. With his addiction, and likely suffering from PTSD6 on top of a tendency to depression, he badly needed to recuperate and heal to save his own life. To do this, however, would mean letting everybody down—possibly even harming their livelihoods. He loved people, hated that his love made him miserable, and ended up hating himself. And this bind was holding him hostage to a career that was killing him.

THE DEATH OF THE DREAM

Despite being subjected to the mainstream, Kurt still maintained contacts with numerous figures in the underground scene. But since the IPUC in August 1991, Kurt had many unresolved feelings toward toward his former home of Olympia and toward those aspects of the underground it embodied. As Michael Azzerad puts it, Kurt “craved the acceptance” of the underground, and he continued to “even at the height of his fame. It was a massive conflict that he never managed to resolve” (Amplifications). As stated earlier, Kurt had begun to develop a serious animus toward Calvin Johnson, leading to an abstract idea of “Olympia” as elitist, puritanical, and judgmental7. This sense of judgment was compounded further by a deep sense of violation and victimization from the press. So in 1992 he decided to make a public statement about his success and to push back.

While the liner notes to Incesticide, entirely written by Kurt, had multiple scores to settle, one objective seems to have been to reply to Olympia—and to abdicate whatever role he felt they expected him to fulfill. The album itself was the first one Nirvana released after becoming famous, and its collection of B-Sides and outtakes was meant, in part, to weed out their fan base. In the note—which more famously stands up against racism, sexism, and homophobia—Kurt begins by discussing a connection he’d made with The Raincoats, a UK post-punk band that was seminal, nearly legendary, in the Olympia scene. This was partly a display of gratitude, and partly a way of boasting before those who would say he wasn’t cool. Then, after establishing further credibility by listing his collaborations with underground bands since becoming famous, he arrives at the real point:

I don't feel the least bit guilty for commercially exploiting a completely exhausted Rock youth Culture because, at this point in rock history, Punk Rock (while still sacred to some) is, to me, dead and gone. We just wanted to pay tribute to something that helped us to feel as though we had crawled out of the dung heap of conformity. To pay tribute like an Elvis or Jimi Hendrix impersonator in the tradition of a bar band. I’ll be the first to admit that we’re the 90’s version of Cheap Trick or The Knack but the last to admit that it hasn’t been rewarding. (emphasis mine)

For me, this marks a significant end. I don’t feel the least bit guilty—that’s what one calls “protesting too much.” But more striking and painful is the fact that, at what is arguably the heart of the statement, he is disavowing the vision of punk rock freedom, a thing that was once almost sacred to him—now it is “dead and gone.” In late 1990 and early ‘91, he’d seemed possessed by a genuine vision, seeking to communicate something that had transformed his life. But in place of that, everything here seems retrospective, finished, and drenched in cynicism: he’s taking a victory lap by admitting defeat. Now, with the sacredness of punk/art/freedom discarded, the only element left from his vision of an affirming musical mission was his belief in passion. But in less than two years time, in his final note to the public, he would announce that even the passion too was dead for him.

But for the moment, Kurt continued on, and the band’s tie to the underground continued too. In late 1993, Nirvana’s appearance on MTV’s Unplugged gave them a chance to cover a song by the Vaselines and to bring on The Meat Puppets for three songs—amazing feats of cultural endorsement for the underground. But elsewhere in that same performance, it was almost impossible not to hear the echo of “sell out” when they covered David Bowie’s “the Man who Sold the World.” Staring into the camera and singing, “You’re face to face with the man who sold the world” made bitter sense alongside “All Apologies,” in which he claimed he’d “take all the blame.” In this indirect gesture, he is posing as the man who sold out the underground, now come to apologize with equal parts irony and confession. It was quintessential Nirvana. But by this time, such dichotomies had grown exhausting, and Kurt had become viscerally, existentially miserable. By April 1994, he was gone. His death was the result of a complex of factors—including heroin addiction, marital strife, and profound mental anguish—but without a doubt it was also the impossible-to-foresee price of his fame, poised as it was dangerously atop a cultural contradiction—a contradiction he had framed for the public to perceive. He’d hoped he could bring the the underground to the mainstream, inhabiting the crux of his cultural position while also enjoying it and controlling it—maybe even weaponizing it. But in the onslaught of fame, these contradictions were amplified, externalized, and enacted by forces beyond his control—market forces, exploitation and commodification, media frenzy and fantasy—and it destroyed his life.

It may be inevitable that we look at Kurt’s suicide with finality and grief. But we should also keep room open for mystery, for a vision where death is not an ending, but a passage and release—it’s there in the band’s very name. Punk rock was art for Kurt, and it is a scared thing to devote oneself to art and the freedom its passion brings. Regardless of how sloppy, noisy, or fucked up it is, no one can tell you you’re wrong as long as you truly believe in what you’re doing—because it sets you free. And such freedom can possess a person with so much energy and faith that it compels them to communicate it to others. And this is what Kurt did. Among the many conjectures about what drove him, I think one objectively true thing is that he absolutely loved the communion of live performance—that this was where he found his joy and freedom. To Michael Azerrad, when he described the transcendent feeling of playing live, he said, “[I]t’s anger, it’s death, and absolute total bliss” (qtd. in Amplifications). This is ecstasy—a standing outside the self, even a breaking outside of the self. And in the grip of that, filled with its mystery and passion, feeling the total bliss in which anger is released and transformed, death ceases to matter as such—because there’s something bigger than that, and you know it. And there can be no fear any longer.

ENDLESS, NAMELESS HISTORY

It has been thirty years since Nirvana ended. But these particular thirty years have advanced with a bizarre mixture of radical changes and absurd stagnation. It’s a platitude to say that the pace of change continues to accelerate, and that the internet drastically reconfigured culture—but from another perspective, how far past Reagan are we, really? If punk broke and history ended in 1991, but neither of these things really stuck, then what actually has been going on? Where are we?

If many factors of the early 90s cultural matrix have shifted and/or vanished in the last thirty years, others have become more monstrous. This is especially true in music. As Kurt foresaw, rock is largely exhausted as a commercial force and is no longer the dominant form of popular music. Alongside this, there is less a sense of monoculture—as once upheld by basic cable, MTV, and radio—and without this, the idea of the “mainstream” becomes harder to define and to disrupt. Additionally, independent music and culture itself have become recast as a mere genre and even a fashion: for many, “Indie” is now an algorithmic preset, just one modality of cultural mass-consumption among others8. This is all the more troubling when we consider that what genuine “indie” culture once opposed—corporate control—has only amassed greater centralized power in recent years. For as the internet, file-sharing, piracy, and streaming severely altered the recording industry, the major labels managed to adapt via conglomeration: now, just three major labels control 70% of the market. And each of these major labels— Universal Music Group/UMG, Sony, Warner Music Group—is a partner with Spotify, who controls an overwhelming amount of our music listening.9 When seen this way, the Corporate Ogre is more powerful than ever before.

Reflecting on many of these cultural changes, Baumgarten’s history of K Records suggests that the old Mainstream vs Underground divide has simply gone out of fashion. For him, writing in 2012, major labels had ceased to generate the same resentment among younger fans and artists as they had “stopped drawing an impenetrable line” between the world of corporate and independent culture. To be fair, both Baumgarten and Calvin Johnson acknowledge that this can be freeing for one’s listening habits and serve as a useful corrective to the some of the monotony, puritanism, and elitism—the paradoxical conformity—that can emerge in punk subcultures. But in our world of Poptimism, streaming sites, and algorithmic playlists—a world in which music is often enlisted as mere mood management and atmospheric wallpapering—the reigning criteria seems to be a kind of shallow, disposable aestheticism10 —or, mere dopamine management. By contrast, the underground was about something more than style, aesthetics, and affect: these did matter, but the line drawn against the corporate world was crucially a material one marking a political rejection of economic exploitation and profit motives. Without this stance against capital, and the fascist tendencies reinforcing its dominance, any supposed independence or opposition one presents as an artist is bound to crumble.

Confusingly, though, fans often expect mega-stars to be somehow immune to their massive wealth and corporate ties. Some even want their faves to be political radicals despite the fact that the profit-motive structures their very careers: they are the CEOs of their own brands. Against the radicalism of the underground, this is the neoliberalism we have all seen fail us for decades now, in which one seeks a compromise between “progressive” politics, professionalized art, and the market. And it is arguably the case that Kurt was the first one to experience the implications of this neoliberal turn within the culture: he walked up to that line where art and advocacy blur with total commodification, he saw just what it was, and it killed everything inside of him. As Nick Soulsby writes, “Kurt’s death was all the more powerful because he died as one of the rare souls to win fame and great fortune only to declare celebrity to be null and void; something to despise and to leave behind” (“Victory”). In a world where the billionaires destroying the planet in a sadistic frenzy of control also insist on being loved and admired as celebrities, one can see within Kurt’s story a harrowing commentary on their soullessness—and on the soullessness of the future they hope to create.

Still, I would not be writing this if I did not have hope. I find hope in feeling that more people are able to see how truly corrosive is the culture we’ve been sold. The masks are off in all areas of public life, and the coordinates are shifting. And despite the forces out to erase it, we do have a living tradition of autonomous culture—not just in music, but in poetry, publishing, art, everywhere. Despite the many negative trends, so many have been keeping the line drawn against capitalism and for the independence of art—they’ve been doing it since the Reagan years, in some case. Many others are rediscovering it today. Zines and scenes and DIY music are thriving. Home music production has exploded in the last decades with the emergence of digital recording and through the direct-to-audience, online storefront of Bandcamp11. Record stores have made a resurgence, housing vinyl as well as zines, books, and community events. There are so many of us who want out of a strictly algorithmic culture and into art and culture that is analog, slow, small-scale—and just more punk in its attitude toward compromising cultural institutions that have proven so inept at standing up to fascism. And this seems all the more crucial at a moment when most of the hideous men who built and/or now own the algorithmic platforms ensnaring culture have seized government and commenced overt destruction of our public resources, not to mention of our planet’s future. And so, for any future worth having, we need a genuinely oppositional culture—a culture of material opposition to capitalism and its institutions and to the bigotry used to legitimize its violence. The culture of neoliberal compromise, in every area of public life, has failed—its moment in history is over.

As we make work to create the future, it still matters deeply how we remember a thing: how we internalize and feel it significance—and how we carry that forward into our lives. And when we look back across thirty years to think about what Kurt Cobain attempted and achieved—about his timing and prescience, his contradictions and ironies, and about how he carried the underground tradition—we can grasp something vital about culture itself and the nature of autonomy. Rather than a source of nostalgia, excitement, and tragedy, we can look to Kurt’s moment as an historical complex in which underground culture and its necessary antagonism with capitalism are given vivid expression. We can look to it as a story about art and how it exists under the commodity form. Because art will always desire something beyond what capitalism will permit: namely, the freedom of living on your own terms, at your own pace, making the art you want—or the community you want, or the love you want—without having to worry about money. We should want more for our art and our culture, and more for our lives, for our memory and desire and history—we should want more even for the dead. And we should make culture from this want, this love, and then keep renewing our contact with it in the fight against commodified reality and its war on the future, on imagination itself. In the end, Kurt may have lost his faith, but I’ll say it for him anyway, because nothing is over yet: Punk is freedom. Art is sacred. Passion saves.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Azerrad, Michael. Nirvana: The Amplifications. Harper Collins, ebook, 2023.

--Come As You Are: The Story of Nirvana. Doubleday, 1993.

--Our Band Could Be Your Life. Hachette, ebook, 2012.

Baumgarten, Mark. Love Rock Revolution: K Records and the Rise of Independent Music. Sasquatch Books, 2012.

Browne, David. Goodbye 20th Century: A Biography of Sonic Youth. Da Capo, 2008.

Clover, Joshua. 1989: Bob Dylan Didn’t Have This to Sing About. Univ. of California Press, 2009.

Cross, Charles. C. Heavier Than Heaven. Grand Central Publishing, ebook, 2012.

--”Requiem for a Dream.” The Life & Genius of Kurt Cobain. Guitar World, 2014.

Goldberg, Danny. Serving the Servants: Remembering Kurt Cobain. Ecco Press, 2020.

Hannah, Kathleen. Rebel Girl. Ecco Press, 2024.

Oakes, Kaya. Slanted and Enchanted. Holt Paperbacks, 2009.

Morgen, Brett and Richard Bienstock. Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck. Insight Editions, 2015.

Ruland, Jim. Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise and Fall of SST Records. Hachette, 2022.

Soulsby, Nick. Cobain on Cobain. Chicago Review Press, 2016.

--"Victory and the Damage Done Part 2: The End of the Rock Star.” Nirvana Legacy. Aug 6, 2013. https://nirvana-legacy.com/category/nicks-philosophies-on-nirvana/page/2/. Retrieved Jan 17, 2025.

True, Everett. Nirvana: the Biography. Omnibus, 2006.

Hanna’s sympathy for Kurt’s position can be explained in part by friendship, but also by Nirvana’s meaningful support for Bikini Kill within Olympia. According Tobi Vail: “We were angry and pushing back against male domination and patriarchy and at that point I feel like most men in the Olympia music scene were threatened by us—exceptions were the teenagers in Unwound and the guys in Nirvana, who were super supportive.”

In August 1991, Nirvana was still just an up-and-coming band: “Smells Like Teen Spirit” did not even hit radio until the last days of the festival. As such, there would have been no concern about oversized crowds or media. And many wanted Nirvana to be there. Tobi Vail’s summation of the moment is valuable here: “For me it was a little bit of a sad time. Nirvana wanted to play and they were not allowed because they had signed to a major label. The ’80s were ending and the ’90s were starting. L7 were great. I was confused that they got to play but Nirvana didn’t. [Note: L7 was on a major label, Slash Records]. I remember wishing that they didn’t sign but understanding why they did. I didn’t think we needed corporations to buy and sell our music and I think that was kind of the main idea of IPU.”

You can see this so vividly and heartbreakingly on 1991: the Year Punk Broke. They were Nirvana, the band we know and love, but they hadn’t been wrecked by fame yet—tho we know what’s coming.

The “No On 9” benefit concert was organized against proposed anti-gay legislation in Oregon in 1992. Kurt and Krist famously kissed one another on stage.

In fact, at the time of Kurt’s death, enormous pressure was being exerted on him by many people to play Lollapalooza, which he adamantly did not want to do. Accounts vary somewhat, but this was reportedly a large part of the rationale behind the regrettable “tough love” intervention that occurred almost a week before his death. By many accounts, it was a disaster that hastened his demise.

According to Cross, a doctor in a rehab facility who treated Kurt suggested he might have PTSD, but it also just stands to reason. Kurt became world famous, got married, and had a child in a single year—these are extreme life changes, any one of which is destabilizing. On top of this, he was deeply traumatized by media attention to his addiction, especially in the Vanity Fair profile on his wife, Courtney Love, which resulted in LA County taking action against them as unfit parents. Eventually, he and Courtney found themselves in a custody battle with the state. For a man who needed privacy, treasured the security of his family, and deeply, viscerally hated humiliation and judgment, these factors just overwhelmed his psyche—which only further fed his addiction.

This feeling was reinforced by Courtney Love, who hated Olympia and was reportedly jealous of Kurt’s closeness with Bikini Kill (esp. Tobi Vail, whom he had been in love with).

As Kaya Oakes notes in her history of indie culture, the aughts gave us punk at Urban Outfitters, Condénast’s Pitchfork, Sonic Youth at Starbucks, Garden State, The OC’s Seth Cohen, and Toyota pitching itself as a vehicle for DIY-ers.

Fundamentally, music has been turned into data—and data is another form of commodification. Data is packaged and sold as a product to those who need it—for any reason imaginable—and so music-as-data becomes not just about what is popular but about surveilling the granular, almost visceral habits of human attention and usage of their devices.

Worse still, the criteria for many is controlled by industry algorithms. They might never know the bands or names of songs they hear, they almost certainly don’t know the label who released it, and some of those songs may not even be made by humans. A recent article in Harper’s exposed a scandalous practice at Spotify where fake artists and AI were used to boost revenues. In response, musicologist Ted Gioia has written, “Our single best hope is a cooperative streaming platform owned by labels and musicians.” Despite coming from a very different world, Gioia’s insistence on cooperative ownership resonates strongly with earlier ideals of the underground.

Sadly, Bandcamp was sold twice to corporations in the last couple years. It’s future is uncertain, and it could change again without warning at any time. A cooperatively owned version of such a platform is what is needed, where the musicians and labels would actually have a say in how the site operates and could prevent such buyouts. Subvert is the most recent attempt to launch such an endeavor, though I know little about them.