Poetry, Fascism, and Imagination

Psycho-materialism against a spiritualizing tendency in US poetry

In the recent Harper’s, poet Christian Wiman has written a review the letters of Seamus Heaney. Normally, I would not pay attention to this, but I got tricked into reading it via a somewhat misleading tweet. The essay is mostly unremarkable, and there is nothing truly egregious about it. Wiman represents a very conservative tendency in poetry, but he is a sensitive thinker who proceeds with humility and evenhandedness. Still, it’s partly these inoffensive qualities that make it such a powerful distillation of American literary ideology: for many, Wiman is speaking common sense in a respectful way, and this makes his essay highly revealing of norms and values. But it goes deeper than that. Yes, Wiman thinks in terms of prestige and “greatness”—he sees Heaney as a quasi-mythical “great poet” who is quoted by US presidents, as if this were something to aspire to—but he also inadvertently shows the limits of a spiritualizing tendency in poetry and the politics that come out of this. Wiman thinks in terms of a dichotomy between the spiritual and the material, and in examining and questioning this, I want to redirect attention to psyche and imagination as world-shaping forces not reducible to either side of his binary. Further, I want to show what this has to do with fascism.

Poetry, Prestige, and Presidents

I will skip past most of the material about Heaney’s letters themselves and focus on Wiman’s interspersed thoughts about poetry and its social role. Essentially, he sees American poets as falling short of what they could achieve, and he holds Heaney up as an exemplar of what one should aim for in a poetic career. He stands in awe of Heaney’s greatness: “Heaney’s career already seems mythic. No English-language poet has enjoyed such fame since Robert Frost, and even Frost’s poetry didn’t have Heaney’s international reach.” Wiman then insists that American poets are falling short of the Irishman’s example, saying that the closest the US has come to producing a poet of Heaney’s stature are Louise Gluck and John Ashbery. He then immediately insists on how weak the comparison actually is:

Heaney’s sales dwarf theirs, for one thing, but it’s more than that. Two US presidents have reached for Heaney’s work for rhetorical ballast and vision. (There’s a wonderful letter detailing the time Bill Clinton barged into Heaney’s hospital room and charmed the whole ward.)

Supposedly, I’m supposed to think it’s a limitation of John Ashbery’s work that Biden can find nothing there worth putting in his speeches? Am I supposed to give a shit about “dwarfed sales,” and—good lord—am I supposed to find Bill Clinton charming? I’m taking some easy shots here, but here is the point: I’ve written on this blog before—with help from the work of Amy Paeth—about the way that mainstream US poetry is conceived as a nationalist enterprise, and how this is institutionalized through the Poet Laureate system. And here, we see all of that laid out as pure ideology: poets and presidents are to share a common vision, and it is an honor to have a president turn your art into “rhetorical ballast and vision” for the American empire. I couldn’t disagree more fully.

This sense that American poets are failing this nationalist ambition persists throughout. He seems to want a “great American poet” who can speak to all people, for all people, across the ages. His fear is that poets have given up on such an ambition. As his essay winds down, he reflects: “A certain diminishment of ambition has set in: poets no longer feel they can or should attempt to speak to all humans—and even, occasionally, beyond that.” He also says this is coupled with a loss of faith, and that this is a loss of faith in “the poetic enterprise itself.” Setting aside the fact that he seems to understand this “enterprise” as amenable to US presidents— and setting aside the fact that the “speech” he is envisioning is fundamentally ahistorical—the full argument Wiman couches all this in relies on a dichotomy between the Spiritual and the Material. And far from being a mere philosophical dispute, this dichotomy poses further political implications that I want to illuminate, while also sketching a different way of thinking about poetry.

Mistaking Psychology, Mistaking Materialism

To see this dichotomy, and to untangle the politics, we have to trace a somewhat intricate line of thinking. First, we should note that Wiman is often characterized—by himself as well—as a spiritually minded poet. He is a Christian, and he writes of the spiritual need that people have which poems and poets can help cultivate and inform. In this particular essay, he writes of poetic gifts as “a gift with spiritual capacities,” and states that “New spiritual experience demands new language.” None of this on its own is a problem for me, and I am not suggestion atheism as a counterpoint. The spiritual is a component of the real, as far as I am concerned, even though I may not share Wiman’s specific views. The problem emerges when he begins to characterize the other side of this dichotomy: the stuff that is not spirit.

When making his claim about “diminished ambition” among American poets, he considers that this has to do with the “psychological” nature of America itself, and of the prevalence of the “psychological self” in our poetry. And according to him, this focus on the self and its psychology is bound up in an insistence on materialism:

America is a psychological country. For all the religious fervor, the intellectual class (and by that I just mean people who take reading seriously) tends to be materialist. . . . For a materialist, the most important existential activity is the realization of the self [Note: This is a drastic leap in logic.] . . . Even people who know nothing about psychology often operate under this assumption, and their lives are arranged toward securing and asserting a coherent self. This makes perfect sense, since if the self has an end (materialism, remember), then the self is an appropriate end in itself.

OK there is a lot here, and most of it is very flimsy. But notice that Wiman links materialism (in his broad definition of this term) with psychology to suggest a self-limiting horizon. In his view, this psychological, materialist limit is at the heart of what brings about the “diminishment” of poetry’s “enterprise.”1 This limit is what he believes can be better addressed by an ambitious poetry that better employs is “gift with spiritual capacities” in a poetic “enterprise” that, as we’ve seen, is fine with a soft nationalism.

Now, I couldn’t help but fixate on this odd conflation of psychology and materialism—and not least because I have written at length about a “psycho-materialist poetics.” Ultimately, Wiman joins these words into a diminished binary relationship with the elevations and expansions of the spiritual, and in so doing suggest his conception of both psychology and materialism is bad. He leaves what I’ve elsewhere called "psycho-materialism” completely unthought, and by digging into this nexus of terms, we can open up something new. Because again, it’s not just about Wiman: it’s about the way his thinking here captures something in American literary ideology, and in how it may get trapped in bad politics not just through overt things (such as seeking prestige, status, greatness, wanting presidents to quote you) but also through more covert things (such as understanding the nature of poetic creation through a bad conceptual binary). And against this, I want reorient us through an emphasis on a neglected third term, psyche.

Imagination Matters

In large part, I follow James Hillman2 on matters of psyche. He is the thinker who has placed the most emphasis on that word and who provides the most expansive definition of what it means and how it operates. Further, he understands it as inherently a poetic faculty, but it’s a poesis that is innate and structures human reality in both conscious and unconscious ways; he sees the mind itself as having a “poetic basis.” For a more detailed discussion of the term psyche, I’ll refer you to the section “Defining Psyche” in my essay on psycho-materialism. But here, I’ll simply say that psyche lives in us, and us in it, through images: it is essentially imagination as it apprehends and shapes the real, such that reality as we know it is a continuous imaginative act—one that we forget is going on. In short, by recovering psyche from erasure—buried in a reductive, self-oriented “psychology” in Wiman’s terms— we can clarify imagination as a forming and deforming force in human reality.3

And here is why I believe it matters: spiritualizing discourses—such as Wiman’s—too often ignore history and material conditions. There is a real hunger in people for something more than the reductions and literalisms of a strict material view point, and they often seek this in spirit as the only alternative. However, imagination/psyche gives another perspective to take. And through psyche, we stay focused on the material and historical world while not reducing everything to merely material. Above all else, psyche is about defying literalism and reduction: it is a solvent for all final vocabularies and fixed systems. And as none other than Hegel shows, this is one fatal aspect of the discourses4 of spirit: they love a system.

In Hillman’s view, psyche is sometimes seen as in dialectical opposition to spirit, and in this, psyche holds much more closely to the material world, to things and objects, and the surfaces and particularities of this world. In fact, for Jung, it is probable that “psyche and matter are two different aspects of one and the same thing.” And in my emphasis, this cleaving to matter also holds psyche close to history and to the images through which it lives and dies5. By contrast, the trap of “spiritualizing” discourses is that they usually want to transcend and leave the material, historical world behind: to find refuge in God, yes, but also in nostalgia, the pastoral, idyls and idealizations; or to focus on “finer feelings,” universals, absolutes. More acutely, though, such spiritualizing discourses are essential to what Benjamin referred to as the “aestheticization of politics” that we see in fascism.

The aestheticized, spiritualized “greatness” of fascism, and its corny fantasies of strength and invincibility, are always at odds with material reality. They rely on the removal, extermination, and oppression of living beings, and they are hostile to the ecological, interconnected nature of life on this planet6. Their psyche is locked into a terminal nightmare fantasy which they overcompensate for with exaggerated but fundamentally lifeless images of strength. They seek to overcome reality through will, imposing it and dominating the real, and this means killing off imagination’s interplay with the particularities and nuances of the material world. There is no care for the imagination here, but a deamonic seizure of idiocy: a fatalistic compliance with a collective pathology that is obsessed with hiding its own absurdities. As such, they always move toward the dead images of static myth—the hardness of the statue, the frozen flesh of the icon—and not the fluent, breathing imagination that makes poetry a legitimate psychology: a true language of psyche, and thus a language whose dreams speak material reality and vice versa.

While I regard Wiman with some derision here given his remarks about presidents, my point is not that he and the literary ideology he espouses is fascist. In fact, I am basically sympathetic to a few of his claims (such as the exaggerated emphasis on the mere individual in poetry). But the danger here is that he legitimizes his poetics in terms that offer no recognition of or resistance to these forces. As such, they abdicate imagination as a ground of struggle, and I believe it absolutely is such a ground. By misunderstanding psyche—and in this instance, by creating a strawman conflation of psychology and materialism—he defaults to a bland universalism. Cordoning itself off in a polite tradition that courts prestige and presidents, such poetry becomes clueless about its actual position. Again, Wiman is no fascist, but that’s just it: if you don’t want to end up with a Roman statue avatar guy in your corner, talking about “the heights of spiritual excellence” and “healthy aesthetic impulses,” you will need better politics. And if you are a poet, that means you need a better psychology—one that understands imagination and positions itself against fascism.

Afterward

As mentioned above, I’ve written about much of this at greater length in an essay called “The Ghost Mine Explodes: Toward a Psycho-Material Poetics.” This essay actually received some attention recently in an article in Community Mausoleum, and that article—alongside my thoughts on Wiman— made me want to reflect on it a bit further. After all, “Ghost Mine” is over two years old, and there are some aspects of it that I would reframe today.

For instance, I do not think a poetics of psycho-materialism is necessarily one that must dwell in nightmare. I do think that nightmare is a good way of conceptualizing what human imagination is up against—the nightmare of a technocratic fascism that destroys art, political possibility, and the ecosphere itself—but there is room for more affect and expressive possibility than doom-laden psychic warfare. At the time, I was articulating a kind of militant psycho-material poetics: a specific strategy for producing a poetry that wars against the degraded, fascist imagination lurking in our historical moment. And that essay leans into that mentality quite heavily. Since then, I’ve become quite interested in psycho-materiality in other modes and forms.

Also, I want to say that “psycho-materialism” is simply a fact of reality: it is a real nexus shaping our experience of the real and it is not limited to an idea of poetics. I say this almost as a position of faith, and I don’t expect everyone to accept it, but it’s how I see things. Imagination and material reality intersect, and what we call spirit is the living energy that keeps it all moving, draws distinctions, and gives life—or that is one way of putting it. These definitions are provisional and only good insofar as they enable your thinking to carry you deeper into how you create and imagine. Holding to psycho-materiality while being mindful of spirit is how I go about it, and it has saved me from a lot of bullshit. It’s possible it’ll do the same for you—but then again, I may just be spinning my own head canon of ideas here. No helping things if that’s the case.

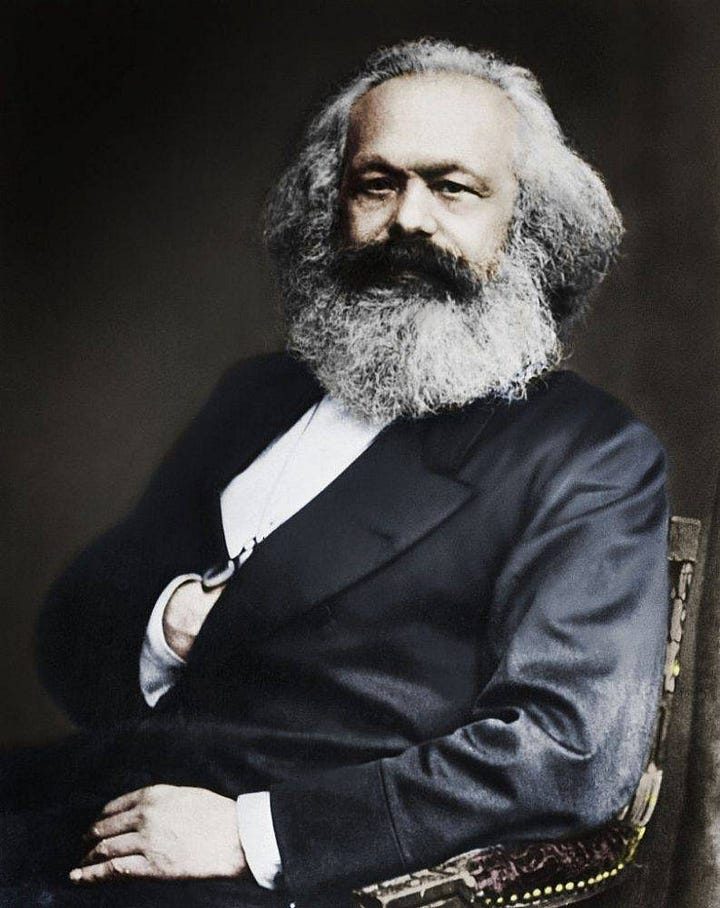

Lastly, the word “Marxist” appears in the opening paragraph of the essay, and I think this throws some people off. I do not think of it as a “Marxist poetics,” at least not in the sense of subscribing to a strict Marxist teleology and program for revolution and trying to fit poetry in there. Instead, what I meant was that the “materialism” side of “psycho-materialism” is informed by Marx’s analysis of capitalism and history as class struggle. But there are too many heterodox elements in my thinking to actually feel comfortable calling it “Marxist,” plain and simple. Ultimately, I think of it in terms of Benjamin’s words on Surrealism and its desire to “win the energies of intoxication for the revolution.” Yes, revolution is in the mix, but only insofar as dreams, poisons, and the imagination belong there too.

Wiman does point at two other factors that lead to poetry’s and poets’s diminished reach and ambition: the pre-eminence of prose and the influence of social media and the internet. I don’t agree with either of these lines of thought either, but they are less central to his argument than this focus on a psychological/materialist self as a limiting factor.

I follow Hillman here, but I have disagreements. As in Jung, there is an insistence is on “archetypes.” And sure, there may be archetypal structures—I may be seized by one right now. But for a poet, deciphering this stuff—getting hung up on identifying Shadow, Anima, Self, etc.—can be a waste of energy. I am much more interested in thinking about “an-archic flows of image and signification.” In short, I want to plug Deleuze & Guattari into Hillman and go from there.

Hillman substitutes the word “soul” for psyche, using them more or less interchangeably. I don’t follow that practice here, as I think it confuses the terminology too far. In short, though, there is a synonymous relationship between psyche, imagination, and soul in Hillman’s terminology.

There’s an entire other essay to be written about the distinction between 1) spirit, psyche, and matter, and 2) the discourses on these. It’s very easy to get confused on this, and it leads to all sorts of errors. That is, one can say all kinds of stuff “about spirit,” when actually what you mean is “this is what happens to discourses about spirit, and to discourses that privilege spirit.” Fundamentally, I don’t think language can fully account for what spirit is, or what psyche is, or what matter is. It can show some ways of how they move, but as for what they are? I wouldn’t presume to say definitively. And this is in fact one reason I love the discourse of psyche: it acknowledges this limit and moves through opposition to fixed, determined, final conclusions. It operates through metaphor, image, and metamorphosis.

Benjamin writes somewhere that history does not decay into narratives but into images.

The 4th footnote in my essay, “The Ghost Mine Explodes,” offers a further delineating of the relationship between spirit, psyche, and fascism.

🔥🔥🔥 it’s funny, I came across this same article with similar thoughts in the last month. Love the expansion

This is great and in the best of ways is making me want to rewrite something I'm working on about Buddhism.