When one becomes critical of poetry’s institutions and culture, it’s easy to get overtaken by one’s own negativity. There is no shortage of stuff to become disgruntled or even outraged about, and this is magnified if you spend time on social media (this was especially the case on Twitter in the years 2019-2022, which were formative for me). In addition to structural and institutional scandals and crises, there is just a lot of basic shittiness out there, and if you are attuned to it, it starts to overwhelm and alienate.

In 2022, when I started Dead Mall Press, I was emerging from a pretty demoralizing period in this regard. I had tuned out of poetry for a while and focused on music, but eventually I realized this resignation was something I had to push back against, or it would just stop my own artistic impulse. But it wasn’t enough just to write anymore: I felt a need to materially enact some of my ideas about publishing and to learn from doing—from physically making. And in a vague sort of way, I believed that there was something vital about the materiality of published objects—and I wanted to understand it1.

While the entire experience has been on a very small scale, so far it has taught me an enormous amount—some of which I am not even fully conscious of. Things happen around and through these books, connections form, time unfolds—among people, in dialogue, through echoes and unknown attention. Each book is a material thing, and yet it involves psychic intensities that exceed its materiality. And making this happen, circulating this experience, becomes an adventure—a cultural one. And I started to recognize others—other poets as well as other micro-press/DIY operations, of which there are so many—who share a desire to keep this cultural adventure alive even in its ephemerality. And this also means making sure it stands against professionalism, institutions, and capital.

As such, I think the right way to look at it, for both writer and publisher, is that both sides are peers in collaboration: they are coming together to create books of poetry, but also to give material life to a culture of oppositional imagination. I am fond of William Carlos Williams’s saying, of the culture of little magazines of the 1910’s-40s, “It’s all one big magazine”—that is, the names change, and not everyone is going to get along, but the work of making and circulating goes on outside the hegemonic lit world. There is a loneliness to it as well as a daring in this attempt to create culture out of little more than paper and whatever network you can pull into shape. Those behind it are driven by a belief in what they’re doing and in the excitement that comes with collaborating with writers—but everyone is a just a person, just as clumsy and searching and brilliant and finite as anybody else.

Really, I think I just want my experience of poetry publication to be closer to that of zine culture. And as such, what I’m advocating is not participating in publishing as such. Arguably, publishing is not just making something publicly available in print: it means making a printed text valid within a larger market with specific codes and practices for its circulation—that is, there are rules determining what gets in. For example, Barnes and Noble and even some “independent” bookstores deal only with books that have an ISBN, bar code, and spine—things zines typically do not have. To be there, it must look like it belongs there—like legitimate merchandise. Commodities are not supposed to raise questions about who made the physical object and where it comes from—and zines very much do. In fact, the zine is often distinguished from more literary small publishing by owning this illegitimacy as a strategy—it enacts its independence materially.

This returns me to a previous post about a debate between Bernadette Mayer and Eileen Myles in the early 80s on the virtues of mimeograph publication. Just like other forms of DIY publishing, mimeo was exciting for its cheapness and ease of access—anybody could make books from home. However, Myles began to argue against mimeo because it looked too amateur, with “low production values.” Mayer’s reply stands as a defense of mimeo and, by extension, of zine/DIY culture more broadly, and I printed it in full in the post linked above. And this was playing out at a crucial juncture in the culture of US poetry, and the rest of the poetry world seems to have sided with Myles. Of course, much more set the conditions for this2. But I find it oddly fitting that right at this moment, a much more professional literary world began to emerge.

Whereas Myles obviously grew dissatisfied and embarrassed by the illegitimacy of mimeo—and as this simply marked a sign of the times for poetry more broadly—I’d like to think that the claiming of and nurturing of this illegitimacy is a significant artistic act in the present. And I am interested in the idea of really claiming this as a strategic position alongside others—a position that stands against the ways the imagination is entrapped in the form of institutional poetry. And yes, imagination is political3—it is not reducible to this political function, but it is nevertheless the case that imagination has a political life. For me, the political life of imagination is why a counterculture for poetry is important. And that counterculture is one that distances itself from the literary professional as such and embraces the freedom and virtues of DIY, of zines, and of certain strains of mimeo culture as well.

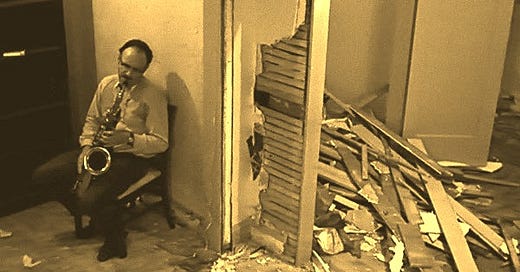

In a sense, yes, I’m arguing for getting out of “legitimate” publishing itself: instead, to make printed texts and to put them into social circulation without falling into the market for literary merchandise and the reproduction of its culture of professionalism. And to do this means that you are involved in a political project as well: the production of your text is engaged in a critique of capitalism and in the creation of a different sociality for readers. Pursued with intention and understanding, this can become a source of inspiration—an intensifier of imagination and poetic activity. I can only speak for myself, but when I say that art is a fight against psychic death, I am only able to say that from this position—an oppositional one, though not one that is trapped in negativity. And as I had learned, trying to believe any of this when participating in the literary-academic world was completely laughable to me. Everything there seemed to deny the politicized psychic intensity I was seeking and the truth that it needed to perceive.

“Psychopolitics is the hierarchy’s gun. / When they point it at you, you better run.” Flipper’s Bruce Loose delivered these lyrics, submerged in the background of their song “Brainwash”4. And it just about sums things up. The present era is enormously precarious for the human psyche, and its survival may be tied up with how we live the political life of art. Right now, this is how it survives for me.

Also, I just wanted to find out if I was full of shit!

Simultaneously in the 80s, personal computers replaced mimeograph, conglomeration was transforming major publishing, small presses began to operate as non-profits and to court donors, many poets moved into university teaching, creative writing programs boomed.

Diane Di Prima wrote, “THE ONLY WAR THAT MATTERS IS THE WAR AGAINST THE IMAGINATION. / ALL OTHER WARS ARE SUBSUMED IN IT.” Tho I see how one could misread the statement, I nevertheless take it as truth.

I’m indebted to Will York for pointing this out in Who Cares Anyway: Post-Punk San Francisco and the End of the Analog Age (Headpress, 2023). The lyric is deeply submerged in the mix, but still audible once pointed out.

the mayer/myles links to not that essay fyi. thank you for writing this, it’s been such a perfectly timed continuation of an ongoing discussion among my poet people here in Portland.

I love this both as a statement and also as a reflection on the history of diy scenes. We’re in a time of both needing the free energy of diy and consciousness of its evolution/coopting. Fun contradiction.

Just personally I’m in a funny place of seeking ‘legitimation’ from sci fi publishing and thinking about what it means for my work. Trying to imagine what my poetry might look like when geared away from conventional publishing.