A Face with No Name

I first became aware of Timothy Carey in John Cassavetes’ The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976). In the film, Carey plays Flo, a thug sent to kill the protagonist, Cosmo Vitelli (played by Ben Gazarra), but due to his obscure fondness for Cosmo, he allows the doomed man to talk his way out of it. During this tense scene, while the two men stand together in a parking garage—both paranoid, fearful, trapped—Carey’s Flo delivers a bizarre monologue that includes one of the all-time comedic lines: “That jerk, Karl Marx, said opium is the religion of the people. Yeah, well I got news for him: it’s MONEY. Money.” The conviction of Carey’s delivery is virtuosic, and he breathlessly segues into the line, “Jesus Christ, my father was right.” In that moment, it felt like the film broke open, and the absurdity of this grim man’s conscience just spilled all over the floor. I knew nothing about the actor, but on the basis of that one scene, Carey had secured immortality in my mind.

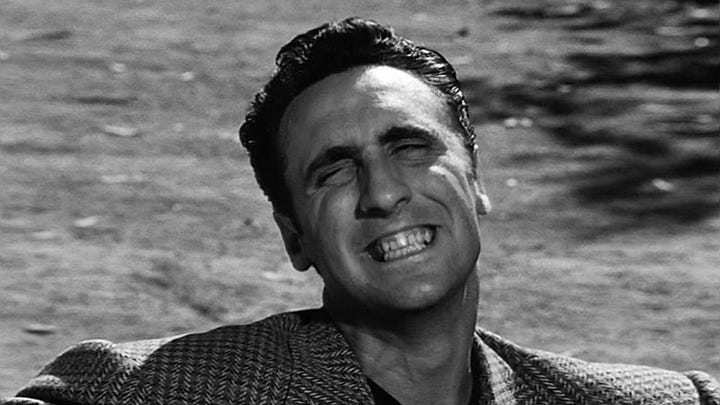

A few months later, I was surprised to recognize Carey in Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory (1957). There, Carey plays Private Ferol, a “socially undesirable” French soldier unjustly sentenced to death for supposed cowardice in the face of the enemy. As his fellow actors were aware, Carey could steal every scene he’s in, often through the use of posture and facial expressions alone. In one moment during the court martial scene, in a strikingly vivid close-up, Carey’s expression seems completely out of place with the scene’s gravity: his facial muscles morph and twitch with sly hilarity and weirdness, and while closing one heavily-lidded eye, the other rolls back to show only white. It’s a bizarre but fleeting moment. And yet, as Kubrick clearly saw, Carey’s eccentric touches work: they strike a note of subtle, surreal burlesque that underscores the film’s argument that war is an insane travesty. And truly, no other actor could be imagined doing that scene in the way he did it.1

Simply put, there has never been another figure like Timothy Carey. Here is someone who blended freakishness & technique, menace & sensitivity, and collaboration & provocation into something almost unclassifiable. By operating on the impossible margin between the iconic and obscure, Carey eked out one of the most singular careers of any actor in the 20th century. As is common to point out, he was the proto-Nicholas Cage: an excessive, polarizing, electrifying presence, and someone who would bring his entire being to seemingly ridiculous, unworthy projects. However, unlike Cage, Carey was a bit player, a mere character actor. And while he appeared in several dozen films and TV episodes, Carey would become just as notable for the films he turned down: these included legendary productions such as Kubrick’s Spartacus and BOTH The Godfather I & II. In what may be the ultimate Carey moment, he required Coppola to write into his contract for The Conversation that the producers come to his house and mow his lawn; somehow, he got the contract—and then quit the film. Such decisions are almost unimaginable for most actors. For Carey, however, they are part of a larger career statement—however incoherent and improvised it may have been—about acting on feeling and not letting the lure of success entrap one’s energies.

To get a better idea of how Carey moved through Hollywood—at once larger than life and almost a nobody—consider that many of his roles, including some of his most well-known, went uncredited. And yet, despite this, his image was indelible. He was very well-known among grindhouse audiences, and he also made wild appearances in mainstream films alongside major cultural icons: he sprays beer in Marlon Brando’s face in The Wild One2 and physically attacks James Dean in East of Eden (see image above). Years later, he could be seen terrorizing The Monkees in the film Head, and he appeared in popular beach films of the 1960s marketed to the growing youth market, such as Beach Blanket Bingo and Bikini Beach. And despite his tense moments with Brando, the actor cast Carey in his own directorial effort, One-Eyed Jacks. He had numerous high-profile fans, including Jack Nicholson, John Cassavetes, Francis Ford Coppola, and Quentin Tarantino (who dedicated the screenplay of Reservoir Dogs to him). Independent artists like John Lurie and Will Oldham both express admiration for him. And he also happened to work with a then-unknown Frank Zappa3, who scored Carey’s first directorial feature, The World’s Greatest Sinner, a film which none other than Elvis Presley loved, going so far as to request a print of it (in typical Carey style, he refused the King).

And so, repeatedly, Carey seems to appear in the brightest of spotlights, embraced by some of the most influential people in the film, only to return once again to obscurity. In the ultimate testament to this Zelig-like quality, a still of his face (from Kubrick’s The Killing) is actually featured in the ensemble of black-and-white cut-outs on the cover the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. While you can’t see it on the actual cover, it is apparently visible in outtake photos positioned just behind George Harrison. He’s there, an immortal among immortals, and yet he retains the luxury of an almost-total anonymity.

Dalí, Cassavetes, and God

Granted, it’s easy to come to the conclusion that Carey simply wasted his career opportunities. And by all accounts, Carey’s behavior was highly bizarre and sometimes confrontational—though people feared him, I never came across any allegations of actual physical violence—and this reputation as a loose cannon closed many doors for him. And despite the usual conclusions people draw about such behavior, Carey lived clean and sober, claiming never even to have smoked. Ultimately, it seems that Carey saw his antics as an important and valid form of expression, and he seemed to have been intentional about them. After all, one of his lifelong idols was Salvador Dalí, and many of Carey’s bizarre moments—from the tame (carrying around a toy monkey everywhere while on set) to the outrageous (pulling a gun loaded with blanks during an audition and firing at Coppola)—are in keeping with a Dadaist/Surrealist commitment to confronting the everyday world with the irrational and spontaneous. Obviously, some of this is just fucked up behavior of a somewhat passé type, and even some admirers admitted he could be nasty and impossible to work with. But the stereotypical conclusion that he was a drug-fueled maniac who wasted his talent is simply wrong. He just seems to have had no interest in drawing a line between life and the stage, and he refused to do the things expected of him as a “professional.”

Another essential element in Carey’s attitude is his idolization of John Cassavetes4, whose rejection of fame and the Hollywood system was well-known. The two men were deeply kindred spirits, and Cassavetes provided a great deal of artistic and financial support for Carey. In a late-in-life interview with Grover Lewis for Film Comment, Carey said he’d turned down the first Godfather film specifically to work with Cassavetes on Minnie & Moskowitz, even though Cassavetes himself told him to take the bigger role.5 He further stated, “The truth is, I never really cared about conventional success. I was probably fired more than any other actor in Hollywood.” When asked by Lewis about the decision to turn down Coppola not once but twice for The Godfather franchise, Carey stated, “But I didn't do either show, because if I had, I woulda been just like any other actor—out for the money.” You can easily find similar statements in Cassavetes’ own interviews. Perhaps there is rationalization in Carey’s answer, but the fact is that a career like his—or like Cassavetes’—does not happen without embracing the power of refusal. Only in refusing popularity, money, and opportunity—only if one largely disengages from the system that makes an artist into a commodity—can one manage to exist like he did: balanced almost impossibly between the Known and the Lost.

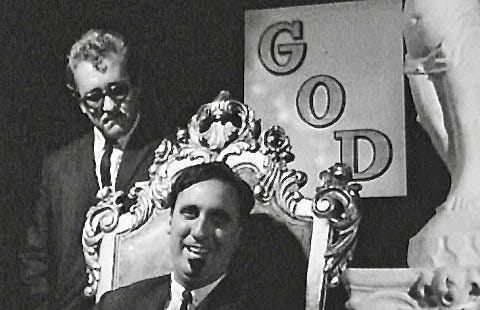

In fact, he explores the absolute collapse of this precarious balance in his only complete directorial feature, The World’s Greatest Sinner (filmed 1958, released 1962): a film delving into the insane despair of the need to “be somebody.” Much has been written about this cult film, and I won’t rehash it all here, but its basic parable is relevant: an ordinary insurance salesman, unsatisfied with his life, pursues fame as a rock-and-roller, re-names himself God (while comically retaining his last name, becoming “God Hilliard”), preaches an atheistic gospel of everlasting life, and eventually enters politics as a dictatorial fanatic before being struck down by the literal God for his hubris. In this story—which many have likened to Eliza Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd, and which is recognizable years later in aspects of Sidney Lumet’s Network—Carey anticipates what Ernest Becker would argue two decades later in The Denial of Death: that human culture, from a psychological perspective, fundamentally consists of “immortality projects.” For Becker, from the Pyramids at Giza to Trump Tower, people create and/or identify with images of deathlessness and “greatness”—flags, symbols, saints, icons, celebrities, heroes, politicians, etc.—to compensate for an unconscious and inescapable terror about their inevitable non-existence. As God Hilliard’s absurdist tragedy shows, any inflated, excessive projection of self ends up being a mechanical travesty of anything truly alive. Carey makes it clear that, for all his fame, Clarence “God” Hilliard is nothing but a puppet of his own gnawing fear of non-being.

Becker’s argument certainly has its limits, and it’s an understatement to say that Carey’s film does too6. But it’s useful in the context of Carey’s larger career to consider that the desire for fame, and complicity with an industry devoted to marketing “stars,” is a kind of denial of reality: a belief that only when others witness and applaud you will your efforts and even your existence have substance. And while imagination is certainly involved in this dreaming of fame, it’s a form of imagination that has been conditioned entirely by capitalism: as though to say, “Only when I am finally a commodity will I be real. Only my popularity (i.e. my market share) can validate me.” Ultimately, this is the corruption of imagination by ideology and consumerist psychology, a point where the commodity fetish becomes entangled with self-esteem. In this way, the very desire for fame—to say nothing of its attainment— can destroy people, and it can destroy art. And even for those who do not want fame for themselves, the love/worship/idealization of others’ celebrity—the belief in the super-reality of The Star’s existence above one’s own—is utterly corrosive to one’s psyche.

We Slip, We Bleed

If Timothy Carey’s career stands for anything, it stands against these tendencies in cultures and individuals. In fact, his refusal of greater popularity may be his greatest artistic statement. By whatever blend of intent, instinct, accident, and luck, his choices as an actor and creator add up to a kind of life-as-performance whose very eccentricity can be a spur to self-examination for other artists. What sort of egotistical dreams do I hold out as a lures for myself, even subconsciously? What kind of compromise am I willing to make, and what kind of opportunity am I willing to turn down? Would I keep doing what I’m doing even if nobody cared or paid attention? Is it the response I get, or is it the process and experience of making that truly excites and drives me? And at the same time, what am I really giving people? And what would it mean for somebody, anybody, to accept it and understand? Often, we can’t truly know these answers. Sometimes the answers are hidden until circumstance brings things forward. Sometimes we simply don’t know the reason for the weird things we do: we do them because we do them. But on some fundamental level of feeling, questions like these are important for connecting to one’s motivations and inspirations and knowing how to weed out the robotic notions, stumbling blocks, and lies.

In his later years, Carey continued doing exactly what he wanted. He lived in El Monte, CA, with his wife and kids and many animals. Hilariously, in his very last years, he was at work on an absurdist play called The Insect Trainer about a cockroach trainer who is on trial for allegedly killing a woman with his flatulence. Prior to this, through the 70s to the early 80s, he had worked on a project called Tweet’s Ladies of Pasadena, about Tweet Twig, the sole man in a ladies knitting club, who roller-skated around Pasadena and rescued and resurrected animals. Cassavetes himself put up most of the money. According to Carey, “Everybody loved the combination [of elements in the project] except the network people who could help me, and they just walked out. I shot thousands and thousands of feet of film, and I spent all of Cassavetes's money, all of my own money. I kept working on it up until about 1981 or '82, and it was like life, you know. We slip, we bleed. Cassavetes taught me that.” He was obviously in love with the project, and was driven by that love against the odds. Surely there was much disappointment in having to leave the project unrealized, unshared, secret to all but a few. And yet he did it precisely as he wanted to do it, and did not compromise to make it marketable. As he said of The Insect Trainer, “I know it's not gonna make it. Somebody else said that, too. . . . But that's the kind of thing I like—something that reaches out.”

Something that reaches out. It’s an ambiguous phrase. In The World’s Greatest Sinner, God Hilliard first captivates the public by interrupting his Elvis-like stage show to fall to his knees with outstretched hand and proclaim, in a frightening, anguished voice, “Please!… Pleease!… Pleeease!… Take! My! Hand!” For Hilliard, it was an invitation to mass delusion and egotistical inflation: it was a hand offering the seed of fascism and fraud. And yet, even as Carey’s critique of Hilliard shows the evil in this, the performance itself exposes the raw human need at the core of everybody: the secret hope that another person will accept the thing one offers from within—that they won’t just refuse you and leave you to your gnawing inwardness. Whether it’s in love or art or simply being a person in the world, the real work is in the courage to reach out, with whatever you have, as long as you’re coming from a place that is honest: to genuinely extend one’s energies into living space, not merely to compel a response for the sake of one’s ego.

Carey saw and responded to the way that John Cassavetes reached out, the way Salvador Dalí reached out. These were his heroes, inspirations, role models. When one looks to Carey, one has to admit that he offers something more difficult to embrace: it’s more fleeting, and it is often awkward, ugly, and baffling, but it’s nevertheless important and affirming. In a society that worships success—a society in which optimization, happiness, and career fulfillment are celebrated adaptations to capitalism’s demands on our energies—the career of Timothy Carey reaches out with an example of maladaptive creative joy. His career is also an eccentric protest, a critique of what it means to be an actor and an artist, and even a human being. It’s an expression of life, and it’s an affirming one, but it affirms things we don’t always want to accept or feel7. It affirms the deep pathos of a struggle to connect: a struggle in which one forges ahead despite not being loved and understood in the way one wants to be, in which one’s projects suffer, in which finances suffer and doors close. In Carey, we see a vivid avatar of all this, a drama in which even his “failures”—his slipping and bleeding—become part of a broader, lived statement: one about careerism, about Hollywood and fame, about art and life. And in this way, we see the entire shape of his career becomes a singular object, an artwork unto itself, and it continues— through unnamable complexities of feeling—to reach out to all of us.

*

References

There are a variety of profiles and interviews I read while preparing this essay, and I link to those below. Additionally, there are some great public access TV clips and scenes from his films to be found on YouTube.

The most informative and well-written sources:

“Cracked Actor: Timothy Carey,” by Grover Lewis (for Film Comment, 2004)

“Timothy Carey: A Genius Out of Both Ends,” by Trav S.D. (for Travalanche, March 11, 2020)

“TIMOTHY CAREY: What A Character!,” by Peter (for Furious Cinema, 2013)

Other valuable sources:

"The World's Greatest Sinner and the Big Timothy Carey Question,” by Jan Lumholdt (for Vienna International Film Festival, 2009)

“Timothy Carey THE WORLD'S GREATEST DIRECTOR!,” by Harvey F. Chartrand (for Film Fax, 2004 ??)

“Criminally Underrated: Timothy Carey,” by Pat Padua (for Spectrum Culture, 2013)

A 1996 profile of Carey by Alex De Laszlo for Uno Mas Magazine, “The Wonderful Horrible Life of Timothy Carey,” appears to have vanished online. However, you can reconstruct parts of it from substantial quotations posted on this fan page.

Basic source material:

This was Carey’s second film with Kubrick, the first being The Killing (1956). Kubrick was apparently indulgent to the actor, allowing him to ad lib (no other actors did this) and get away with eccentric behavior on and off set. But there was eventually a breaking point: Carey was fired after he faked his own kidnapping to drum up notoriety for the film. He arranged for himself to be found one morning tied up and gagged in a public place (!!).

Details are kind of hazy, but it seems Carey was the one who suggested this—he claims he always made suggestions to directors and fellow actors, one of the reasons he often got fired—and somehow he got it in the film. He was a mere extra, and Brando was wary—not to mention intimidating—but he got it to happen.

In an early appearance on The Steve Allen Show, a young Zappa refers to Sinner as “the worst film ever made.” Ironically, Zappa’s own first feature film, Frank Zappa’s 200 Motels, would be publicly derided by his disgruntled co-director as “the worst film in the history of western cinema.”

The word is not too strong. In an interview on Art Fein’s Poker Party, he ranks Cassavetes alongside his other idol, Dalí, and none other than Socrates.

At the time, Carey was also working on an ill-fated TV project of his own, Tweets Ladies of Pasadena, as described later in this essay. And according to a profile by Harvey Chartrand in Film Fax, it was because of Tweet’s Ladies and not Minnie and Moskowitz that he passed up The Godfather. All three were roughly going on at the same time, so it’s hard to say. Regardless, the very real possibility of this is as perfect and hilarious as anything else the man did.

The flaws in the film can be explained by the fact that it was essentially unfinished. According to co-star Gil Barreto in an interview with Harvey Chartrand for Film Fax, “Tim kept on shooting until about 1965 and stopped, because he ran out of money and the guy wouldn't give him any more." Chartrand goes on to add: “Even though Sinner was barely released in 1962, Carey continued working on it—re-editing the footage and shooting new scenes—for the rest of his life.” Cassavetes himself refers to this in an interview, describing a friend who has been editing the same film for almost ten years, and editor Ray Carney says that this friend was Carey (in Cassavetes on Cassavetes).

The most literal example of this is in his later-in-life obsession with flatulence and his quasi-religious insistence on the importance of not holding back one’s farts. The Insect Trainer is based in this burlesque philosophy of gas, in which the repression of flatulence is the source of all our ills. Ray Carney, a scholar of Cassavetes’ work, wrote a letter to Carey after reading The Insect Trainer, and he offers as sympathetic and affirming a read of it as is possible: “What an extraordinary, weird, wonderful, bizarrely unclassifiable work you've created. In the Joycean, Swiftian, Salvador Dalian vein, you violate all of the taboos, cross all of the boundaries, break all of the rules . . . It's a celebration of eccentric, non-homogenized, non-normalized humanity. An expression of love for the lost and forgotten feelings and impulses of life. A recognition of some of the sadness and loneliness of all originals, pioneers, inventors. In short, you break up the mental and spiritual constipation that afflicts both art and life." (qtd. in Chartrand’s article for Film Fax).

loved your piece!!!!! his filmography is interesting, as is his face. i gotta do a deep dive!!

I always like to see when attention is paid to Timothy Carey. I plan to run a piece on his directorial debut, The World’s Greatest Sinner, some time in the next couple of months.